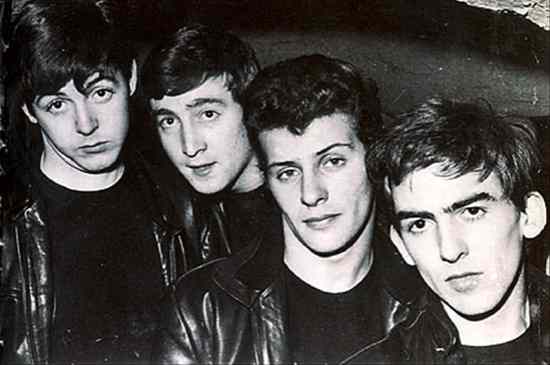

The Beatles success was a bummer for the drummer they left behind. Bounced by the Beatles and replaced by Ringo Starr, Best felt the full pain of his exclusion when the band went nova in 1964, with six number-one singles and a hit film, A Hard Day’s Night. By 1968, the Beatles had the number-one song of the year with “Hey, Jude” and Best had a job with the British civil service. So why did Best get the boot? The drummer said he was never given a reason, but the primary theories are 1) his drumming stunk, a notion Best denies; and 2) the lads just didn’t like him.

The so-called “Elephant Man” had a face his mother could love, but his stepmother? Not so much. Two years after his devoted mom died, Merrick’s dad got remarried to a woman who despised her unsightly stepchild. The second Mrs. Merrick “was the means of making my life a perfect misery,” wrote Merrick in his autobiography. He was forced to quit school at thirteen and take a job as a cigar maker, but his ever-worsening deformity made his right hand too heavy and clumsy to handle the task. Merrick’s vicious stepmother finally persuaded his father to kick the boy out of the house, and a few years later he was being displayed as a museum freak. As dreadful as that sounds, it was actually a break for Merrick, who was treated far better by showman Tom Norman than he’d been treated in his last year at home.

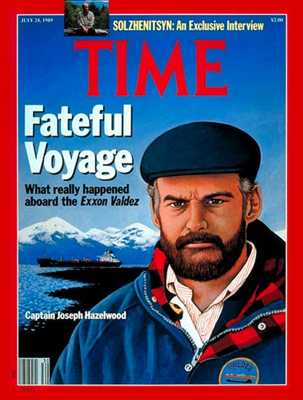

Hazelwood’s oil tanker runs aground, spilling 11 million gallons of crude oil, 1989. The captain of the Exxon Valdez became environmental enemy number one when his oil tanker dumped it’s load on Alaska’s Prince William Sound. Hazelwood, 43, was rumored to have been drinking at the time, although it was the third mate who was piloting the ship during the accident. “Demonizing me works for people,” Hazelwood told the New York Times, in 1999. “It’s a way to personalize this catastrophe.” The spill fouled 1,300 miles of pristine shoreline and killed an estimated 2,800 sea otters, 300 seals, 250 bald eagles and 250,000 other birds. Hazelwood was fired by Exxon and financially ruined by legal costs.

Called a coward after surrendering Fort Detroit in the War of 1812, Hull had his death sentence commuted by President Madison. Still, he wasn’t going to be riding in any military parades. The general’s travails began after he invaded Canada with 2,500 men in the opening campaign of the War of 1812. He was beaten back by British forces three times in Canada, and scurried back to Detroit a month later. Convinced that the British were bringing heavy forces, he fought only briefly before surrendering the fort to an enemy that wasn’t nearly as formidable as he had thought. The only American general sentenced to death, Hull later claimed he had to surrender Fort Detroit to protect civilians.

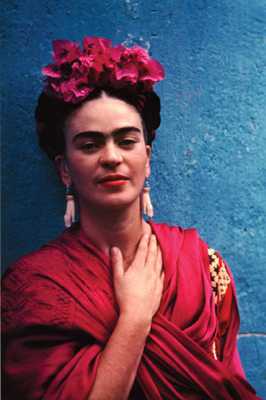

A near-fatal bus crash made Kahlo intimate with what she expressed so well in her paintings – pain. A medical student riding a bus from Mexico City to Coyocán, she suffered multiple fractures to her right leg, a dislocated right foot and shoulder, and injuries to her uterus that make her unable to bear children. Kahlo took up painting during her long convalescence, and soon exhibited a skill for creating powerful, disquieting images. Fifty-five of Kahlo’s one-hundred-and-forty-three paintings were self-portraits, including 1944’s The Broken Column, which showed her in a steel corset that had replaced her damaged spine, and 1946’s The Little Deer, in which she appeared as a deer with nine arrows in her body.

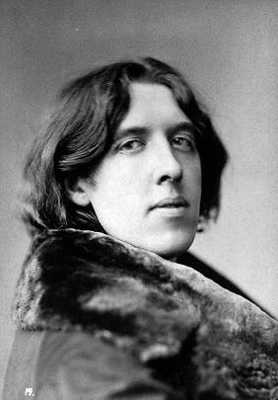

The wittiest of writers, Wilde had no bon mots to placate the homophobic British court that sentenced him to two years of hard labor for “sodomy and gross indecency.” Eight months after debuting The Importance of Being Earnest, Wilde’s public life was all but ended by accusations brought by the Marquess of Queensberry. The father of Lord Alfred Douglas, Wilde’s lover, Queensberry called the playwright a sodomite in a letter. Wilde sued for libel, but was put on the defensive when Queensberry accused him of violating an 1885 law that criminalized homosexual relations between men. Wilde emerged from two years in prison a social outcast with no money and failing health. His writing career destroyed, he died in 1900.

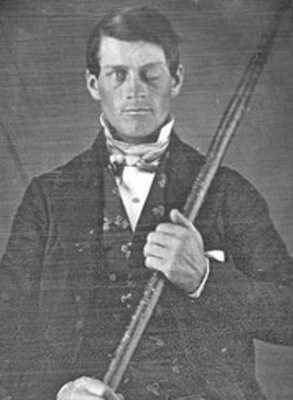

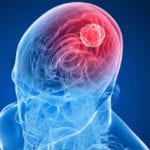

Poor Phineas. A fourteen-pound, three-and-a-half-foot long tamping iron shot through his brain, and all people can say is, “what a breakthrough for science!” The foreman of a railway construction gang, Gage, 25, survived the accident, which puzzled doctors at the time. He’s now considered a legend in the annals of neurology because his case broke new ground in the understanding of brain functioning and personality changes. That was good for neuroscience, not for Gage: He went back to work after ten weeks in a hospital, but he wasn’t the same easygoing chap he used to be. The post-injury Gage was subject to wild mood swings and eventually lost his job. He wandered from one place to another after the accident, dying in 1860 at the age of thirty-seven.

If history had taught us anything, it’s that one should never marry a woman nicknamed “The She-Wolf of France.” Edward’s wife, Isabella, and her lover, Roger Mortimer, staged the king’s overthrow, and that wasn’t the worst of it. While imprisoned at Berkeley castle, Edward II was murdered, either by smothering or by the insertion of a red-hot poker in his rectum. Edward had been a rotten king, more interested in cavorting with his friend Piers Gaveston than with running the country, and probably wasn’t much of a husband either, although he did have four children with Isabella. With Edward II out of the picture, his fourteen-year-old son took the crown; Edward III eventually avenged his father by having Isabella removed from office and Mortimer executed.

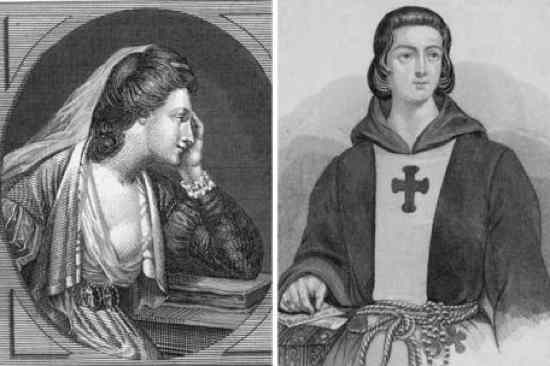

Most men would yell and scream – in a high-pitched voice – if they got their jewels lopped off, but Abelard, 38, took it philosophically. “How justly God had punished me in that very part of my body where I had sinned,” wrote the French philosopher in The Story of My Misfortunes. Abelard’s affair with the teenaged Heloise is celebrated as one of the great love stories of the Middle Ages, but the girl’s uncle and guardian didn’t see it that way. After his niece got pregnant, Canon Fulbert sent some goons to redecorate Abelard’s private parts. After the slashing, the theologian-philosopher began a monastic life.

As if a normal lobotomy weren’t bad enough, Rosemary, 23, suffered a bungled operation that left her “permanently disabled, paralyzed on one side, incontinent and unable to speak coherently.” So wrote Nellie Bly in The Kennedy Men: Three Generations of Sex, Scandal, and Secrets. Rosemary didn’t need her frontal lobes messed with – she was mildly retarded, not mentally ill – but her father, Joseph Kennedy, thought she might bring shame upon the family. “Rosemary was a woman, and there was a dread fear of pregnancy, disease and disgrace,” wrote Laurence Leamer in The Kennedy Women: The Saga of An American Family. Some consider Rosemary’s sloppy surgery the first act in the so-called “Kennedy Curse”: Joseph Jr. died on a World War II mission, Kathleen was killed in an airplane crash, and John and Robert were assassinated in the sixties.