The Angels of Mons is a popular legend about a group of angels who supposedly protected members of the British army in the Battle of Mons at the outset of World War I. The evidence suggests that the story is fictitious, developed through a combination of a patriotic short story by Arthur Machen, rumors, mass hysteria and urban legend, and also possibly deliberately seeded propaganda. The stories of angels themselves certainly boosted morale on the home front as popular enthusiasm was dying down in 1915 and demonstrate the importance of religion in wartime.

Kuchisake-onna (“Slit-Mouth Woman”) refers to both a story in Japanese mythology, as well as a modern version of the tale of a woman, mutilated by a jealous husband, and returned as a malicious spirit bent on committing the same acts done to her. During the spring and summer of 1979, rumors abounded throughout Japan about sightings of the Kuchisake-onna having hunted down children. In October 2007, a coroner found some old records from the late 1970s about a woman who was chasing little children, but was hit by a car, and died shortly after. Her mouth was ripped from ear to ear. It is believed that she caused the panics around that time.

The Y2K bug was the fear that the clocks in computers would fail on the first day of the year 2000 causing worldwide catastrophe. While no globally significant computer failures occurred when the clocks rolled over into 2000, preparation for the Y2K bug had a significant effect on the computer industry. Countries that spent very little on tackling the Y2K bug (including Italy and South Korea) experienced as few problems as those that spent much more (such as the United Kingdom and the United States). The total cost of the work done in preparation for Y2K is estimated at over 300 billion US dollars – for a problem that really wasn’t there.

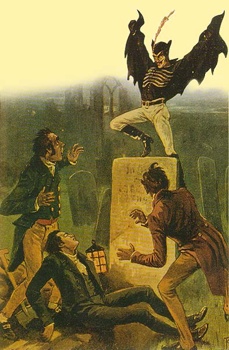

A man was returning home one night in London in 1837, and saw a strange figure jump over the fence of a cemetery and land in front of him. He also reported to the police that the figure had a strange look to him. He had pointed ears, a long nose, and glowing eyes. Several months later, a young woman was attacked by a strange creature in an alley. He gripped her arms and tried to kiss her. She reported his hands were cold and clammy. The woman screamed, and the man ran off. Many people heard her screaming and came to the rescue, but nothing out of the ordinary was found. This story grew as it spread. It eventually turned into another ending: the man ran in front of a carriage and jumped over a 9 foot fall fence. The mayor didn’t take the stories seriously, and assured everyone if it was anything, it was just a man who would be caught. Another girl reported a creature fitting the description came into her house and attacked her. Many, many more people reported being attacked by Spring Heeled Jack (the name given to the creature), but the legend eventually turned into a myth.

The London Monster was a name for a man who attacked women in London between 1788 and 1790. For the first accounts, women explained a man followed them and stabbed them in the back and butt. Some women claimed the man had knives tied to his knees. It’s true that many of these women had ripped clothes and injuries. When this became popular and people realized the Monster only seemed to attack beautiful rich women, girls began to injure themselves and say the Monster attacked them to get attention. A man named Rhynwick Williams was eventually accused of being the Monster, and even though no sufficient evidence was brought against him, the public jeered at him and supported the prosecutors. Williams was convicted and got 6 years in prison. Reports of the Monster continued even after Williams was in jail. Now, historians have doubts if the Monster even existed.

In 1976, a single typewritten page began circulating in France, stating a number of food additives were carcinogens. Copies found their way into England, Africa, Germany, and many other places. What scared people most was that citric acid was on the list, which is in many, many fruits. Books and other leaflets copied the same information over without checking the sources or the facts. These flyers were passed out in schools, hospitals, and health clinics until the late 80s. The leaflet caused mass panic in Europe in the late 1970s and 1980s.

A gathering of parents at a school in 1988 started it all. A mother mentioned that since school started, her child had been looking pale, had headaches, nausea, vomiting, and dark circles under his eyes. Many parents, over time, began to see the same symptoms in their children. After the school was evacuated for a gas leak, the parents suspected the school had something to do with it. Tests were done, and all came back negative. Experts said the parents redefined common childhood illnesses, and may have even imagined some symptoms. None of the children ever complained of feeling ill.

Satanic ritual abuse refers to a moral panic that originated in the United States in the 1980s, spreading throughout the country and eventually to many parts of the world, before subsiding in the late 1990s. Allegations of SRA involved reports of physical and sexual abuse of individuals in the context of occult or satanic rituals. At its most extreme definition, SRA involved a world-wide conspiracy involving the wealthy and powerful of the world elite in which children were abducted or bred for sacrifices, pornography and prostitution. SRA has been described as a moral panic and compared to the blood libel and witch-hunts of historical Europe, and McCarthyism in the United States during the 20th century.

In the late 1930s, two girls reported being attacked by a man carrying a mallet and wearing bright yellow buckles on his shoes. When more and more people reported seeing the man and being attacked, the weapon turned into a razor or knife. The city ended up nearly shutting down when Scotland Yard was called, and suspicious looking people were beat up. Finally, a woman who had reported him earlier admitted to doing the damage to herself. Police began arresting people for false reporting, and the hysteria slowed down.

Fan death is a South Korean urban legend (also found in Japan) which states that an electric fan, if left running overnight in a closed room, can cause the death of those inside (by suffocation, poisoning, or hypothermia). Fans manufactured and sold in Korea are equipped with a timer switch that turns them off after a set number of minutes, which users are frequently urged to set when going to sleep with a fan on. This is so widely believed that the press report it as fact: “The heat wave which has encompassed Korea for about a week, has generated various heat-related accidents and deaths. At least 10 people died from the effects of electric fans which can remove oxygen from the air and lower body temperatures” [Korea Herald, July 28, 1997] This article is licensed under the GFDL because it contains quotations from Wikipedia.