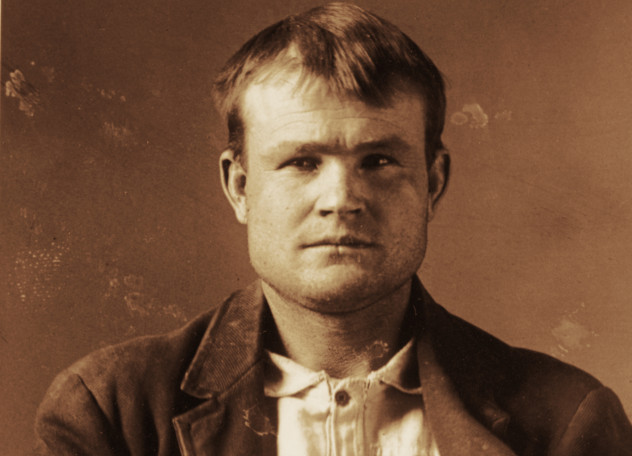

10 Butch Cassidy

The most famous version of the story is the one that was immortalized in the movie starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford as the infamous outlaws. According to that story and other accounts, the pair fled from the United States to Bolivia when the heat from their 1890s spree of robberies got to be too much. It was in Bolivia that they were supposedly killed in a shootout. That’s absolutely not the final word, though. According to Cassidy’s sister Lula, she’d heard stories of a number of his acquaintances who had run into him well after the reported date of his death in 1908—including herself. In 1925, Cassidy supposedly appeared at a family reunion that included Lula, their brothers, and father. Documents uncovered by historical researchers suggest that the confrontation with Bolivian authorities happened in a home while Cassidy and his gang were sorting through the spoils of a payroll heist. Two men were dead in the end, but it’s been suggested that neither of them was actually confirmed to be Cassidy or the Sundance Kid. Some believe that Cassidy shot his long-time partner rather than see them go to jail. Other stories say that he escaped, gave up his life of crime, and lived either in Paraguay, Chile, or Spokane, Washington for decades. That idea is given a bit of credence by the research of Bolivian president Rene Barrientos, who concluded that the story of the shoot-out was completely fabricated. Among those who didn’t believe it were the Pinkerton detective agency, who searched for the outlaws well past 1908 and believed they were killed in Uruguay. Cassidy’s sister maintained that he died in Washington in 1930 of pneumonia.

9 Chief Cochise

Chief Cochise is one of the most well-known figures in the conflict between the Native American people and the European settlers who constantly pushed westward. For someone so prominent whose name is so well-known, he’s a figure shrouded in considerable mystery. Almost nothing is known about his life before the middle of the 19th century when he was already established as the leader of the Chiricahua Apaches in the areas of northern Mexico and southern Arizona. Decades of raids and conflicts between the Apaches and the settlers in the area ultimately led to the creation of a reservation on the southeastern edge of their territory. Cochise died in 1874, only two years after the establishment of the peace he’d rarely seen. The location of his traditional burial somewhere in the Dragoon Mountains was known only to a handful of his contemporaries who never divulged the coordinates. Several legends have grown up around the burial of the great leader. According to the story, Cochise’s dog and horse were both shot to be buried with him to keep the animals from being a public reminder of him and his death.

8 The Lost Cement Mine

Though accounts disagree about how exactly the Lost Cement Mine was discovered, there’s one point of agreement between all the stories: The site was loaded with gold. One account of the mine, written in 1879, says that it was discovered by two men headed to California in 1857. They broke away from their caravan, sat down by a stream to rest, and saw a massive amount of gold. One of the men—the other couldn’t believe it was gold—took about 5 kilograms (10 lb) of it with him. By the time he had reached California, he’d become incredibly sick. He used the gold and a map to pay for his treatment. The other account was written by Mark Twain. According to that story, the finders were three brothers from Germany who were hiding in the mountains to escape an attack on their caravan when they found the gold. Either way, countless prospectors descended on the area looking for the mines. While the Lost Cement Mines have indeed taken on something of a legendary status, there are records of a Dr. Randall finding red rock that was rich in gold in the area. In 1869, two men arrived in Stockton, California. They replenished their supplies, then headed out again. Between 1869 and 1877, they returned each year with a sizable amount of gold. It wasn’t until the fall of 1877 that one of them told an incredible story to a priest before he died. He said that he and his companion had been mining up in Mammoth Peak, then known as the Pumice Mountain. They had found the legendary gold and mined somewhere in the neighborhood of $400,000 worth of it over the years. He didn’t say any more about it—aside from the fact that they had shored up their spot and hidden it from other prospectors—before he died. It might seem like the stuff of fairy tales today, but Bodie, California, one of the areas explored in the hopes of finding the Lost Cement Mines, was the site of the discovery of gold deposits that ended up totaling more than 28,000 kilograms (60,000 lb).

7 Albert And Henry Fountain

Albert Fountain was an educated man, a former solider for the Union Army, and later a state senator for Texas. Educated at Columbia College in New York, he was also a judge, district attorney, lieutenant governor for Texas, and a journalist. In a nutshell, he was a man who made a lot of enemies. Fountain disappeared in February 1896. He and his eight-year-old son Henry were heading from Lincoln, New Mexico to Mesilla. He had been involved in the prosecution of cattle rustlers, and everyone who knew him feared for his safety—except for Fountain himself. According to a mail carrier who had seen Fountain and his son, he also mentioned that there had been a group of riders behind them, but knew nothing more than that. No physical traces of Fountain or his son were ever found, although his wagon was recovered along with a blood-soaked handkerchief. No charges were ever made in the disappearance of Albert Fountain, although there was speculation about what happened. Some people blamed associates of the cattle rustlers while others pointed the finger at Black Jack Ketchum. Other theories put the blame on a part-time United States Marshall and land developer named Oliver Lee, who was eventually tried and acquitted for the disappearance of eight-year-old Henry.

6 The Lost Ship In The Desert

If there’s any place you don’t expect to find a lost Spanish galleon, it’s probably the Colorado Desert. But in the 1870s, there were rumors galore about the lost ships. According to the Los Angeles Star, a treasure hunter finally found what he was looking for in November 1870. On December 1, a man named Charley Clusker claimed to have found an extraordinarily well-preserved Spanish galleon, but nothing was ever brought back from his expeditions into the desert. The ship was a pirate vessel and the treasure was still on board. It might sound insanely farfetched, but there’s a small possibility that there actually was truth in the story. The Salton Sink is a massive depression created millions of years ago in the Colorado Desert, a depression that has been known to turn into a lake. Evidence of flooding includes the presence of oyster beds high in the San Felipe Mountains. It’s possible the pirate ship made its way up the Gulf of California and then ran aground. The crew would have ultimately died, leaving the galleon baking in the sun. Whether or not that’s really the case is still up for debate, but the sheer number of reports about a lost desert ship are enough to spark the imagination.

5 Jean Baptiste

In 1862, Brigham Young and his congregation were presented with a problem. After discovering that the gravedigger Jean Baptiste was also a grave robber, the people of Salt Lake City had to decide what to do with a man who was a thief of the worst kind. Hundreds of sets of clothing were found in his home, stripped from the bodies of the people he had helped bury. Young reassured his congregation that those who had been buried naked by Baptiste would be fully clothed during their resurrection. Baptiste’s trial seems a pretty cut-and-dried case. He was ultimately exiled to a barren island in the middle of Salt Lake, escorted there by a handful of men who had been forced to promise that they wouldn’t kill him on their way there. Even though the lake was extremely low, Baptiste couldn’t swim and he was effectively imprisoned. Or so it was thought. Three weeks later, the owners of the cattle on the island returned to check on Baptiste and their herd. Baptiste was gone. The only signs that anyone had been there was damage to the island’s only shelter, a small shack, and a young cow that had been slaughtered. Baptiste was never seen again. A handful of different theories have been put forward as to what really happened to him. Some believe that he died trying to make his escape, a theory that’s supported by the discovery of a human skull nearby at the mouth of the Jordan River, and later the rest of the skeleton that was still wearing its ball and chain. Then again, no one seems to know for sure whether or not Baptiste was wearing a ball and chain when he was left on the island. Others suggest that he made it to shore on a raft made of pieces of his shelter and the skin of the cow he killed. Some think that he hopped on a train and headed to California, while others think he made mining towns his home. Later reports dated to well after his exile claim that his ears were cut off and his face was marked with the words “Branded for robbing the dead,” but the truth in those claims is as much of a mystery as his fate.

4 Henry Plummer’s Gold

There was no such thing as a background check in 1863. If they’d had such a thing, the town of Bannack, Montana probably wouldn’t have elected Henry Plummer as their sheriff. The gunslinger had already been charged with murder, and it was that jail sentence that he was on the run from when he showed up in Bannack. Not wasting any time, he deputized a few of his outlaw associates. His only other deputy, an honest man he’d inherited, had an unfortunate accident involving a hail of bullets only a month later. Right before he settled down in Bannack, he married a woman named Electa Bryan. His marriage didn’t keep him from working both sides of the law, though, and he used his position as sheriff to confiscate gold from local miners. Once he had as much gold as a mule could carry, he’d head out to a secret location and stash it for later. There’s only a vague idea where he stashed his ill-gotten gains. The treasure’s rumored to be in the neighborhood of $200,000 in gold near Birdtail Rock. His wife admitted that he’d stashed another part of his fortune somewhere along a creek that ran into the Sun River. There was a $50,000 haul from a stagecoach robbery that was purportedly buried somewhere along Cottonwood Creek, and $300,000 in gold near Cascade. None of it was ever recovered. Plummer was only sheriff for about a year before he became the target of town vigilantes who also ensured the outlaw deputies met their end—at the end of ropes. Plummer himself was hanged on January 10, 1864. The knowledge of the location of the treasure died with him.

3 Tom Horn And The Murder Of Willie Nickell

In 1980, Steve McQueen immortalized the story of Tom Horn in his movie of the same name. Horn was a mix of an outlaw and lawman. In the 1890s, the previously lucrative business of cattle ranching had taken a major hit. It had grown much, much bigger than its demand, and the ranchers’ solution of buying more cattle made the problem even worse. Not willing to blame themselves, they blamed cattle rustlers for their hardships, and hired men like Tom Horn to take care of the problem, one way or the other. Horn undoubtedly killed men, but just how many isn’t known. He was hanged for the murder of Willie Nickell, a murder he probably didn’t commit. No one could quite prove his innocence or his guilt, and no one knows who did fire the shots that killed 14-year-old Willie Nickell. After the death of Willie Nickell, Horn’s reputation preceded him as far as United States Marshal Joe LeFors was concerned. LeFors was hired to investigate the shooting and met with Horn under the pretense of a job hunting cattle rustlers. Drunk and more boastful than ever, Horn reportedly made some incriminating statements that suggested he’d been responsible for the shooting. It was enough to put him on trial, and in spite of the defense arguing that every bit of evidence was circumstantial, he was found guilty and hanged on November 20, 1903. Ninety years later, the case was reexamined in a mock trial format and it was found that it was unlikely that Horn had anything to do with the killing. The details of the fate of Willie Nickell aren’t known, but the Nickell family had been part of a long-standing, neighborly feud, and it’s suspected that the killing had something to do with the feud.

2 Queho

Queho was an enigmatic figure who wavered between serial killer, boogeyman, and scapegoat. Not much is known about his early life—or his life at all, really. He was born sometime in the 1880s, the child of a Native American mother and an unknown father. His mixed heritage made him an outsider from the beginning. His first experience with murder was said to have been when he killed his brother, Avote, for killing another man. He left his home in Colorado and headed to Las Vegas, still a blossoming frontier town, sometime around 1910. It was there that he was completely corrupted by whiskey, and it wasn’t long after that his name was used to scare children into being good and dragged up in association with unsolved murders. Within a few years, any mysterious miner death was being ascribed to Queho. He soon had a $2,000 bounty on his head and wisely dropped out of sight. In February 1940, a mummified corpse was found in a cave not far from Hoover Dam. Based on its double row of teeth it was declared to be the elusive Queho. His remains traveled around for a while, used as the centerpiece of a Las Vegas Elks replica of his cave and later stolen, scattered, then recovered. He was finally buried, but it’s still unclear whether he was guilty, falsely accused, or perhaps a combination of the two.

1 Pancho Villa’s Body Parts

Francisco Villa, better known as Pancho Villa, made the impressive rise from bandit and outlaw to respected military leader over the course of a few decades. By the end of his life, he was one of the most infamous figures of the Mexican Revolution. He had already retired from both outlaw and military life in 1923, but his successor was worried about his existence even as a retired rancher. Sure enough, Villa was assassinated. He was buried in Chihuahua, Mexico at Hidalgo del Parral. Three years later, his tomb was broken into and his body was decapitated. It’s never been discovered what happened to his head, but there are many stories and rumors. According to Villa’s granddaughter, there was more than just his head missing when his body was disinterred to be moved to Mexico’s Revolution Monument. When his remains were moved in 1976, his family says only a few bones were left. It’s been suggested that the bones found in the grave weren’t his at all, and that his widow had arranged for the rest of his body to be moved after the theft of his head. The body was then replaced with the body of a nameless woman who had made her way to Parral. There was no one there who knew her name, much less anyone that was willing to claim and bury her body. She was beheaded and placed in Villa’s grave as a decoy for anyone else who tried to desecrate the grave. So, where did the bones end up? A pawn shop in El Paso claimed to have his trigger finger for some time, and it was for sale for $9,500. According to another rumor, his head ended up in the possession of Yale’s secret Skull and Bones Society, but a potential buyer for the trigger finger claimed to already own the skull of the famous revolutionary. It’s doubtful these remains will ever be positively identified as Pancho Villa. Read More: Twitter