Here are some lesser-known facts about The Twilight Zone franchise which are “submitted for your approval”—a phrase which, although heavily associated with the show, was only actually uttered by Serling three times.

10 The Iconic Theme Song Was Not Introduced Until the Second Season

Even people who have not seen The Twilight Zone are familiar with the catchy “dee-dee-dee-dee” of the theme song. However, this song was not actually used during the airing of the first season of the show. The original theme was written by Bernard Herrmann, known for his collaborations with Alfred Hitchcock on films such as Psycho (1960), and while it was fittingly creepy, it didn’t pack much of a punch. CBS was on the search for a new theme, and Lud Gluskin, the show’s director of music, hired Marius Constant, who usually composed ballet scores, to give it a go. Constant came up with two pieces of music, “Milieu No. 2” and “Étrange No. 3,” which Gluskin then joined together to create the new title theme. The song became integral to the identity of the show. Although the theme has been revamped in the various iterations of The Twilight Zone, the memorable four-note guitar riff is always present.[1]

9 The Origin of the Title

The Twilight Zone was so impactful that its name is now shorthand for describing surreal and mysterious situations. When asked about how he came up with the title, Serling replied, “I thought I’d made it up, but I’ve heard since that there is an Air Force term relating to a moment when a plane is coming down on approach, and it cannot see the horizon. It’s called the twilight zone, but it’s an obscure term I had not heard before.” Watch this video on YouTube Serling may have heard (and then forgotten) the phrase when he served as a paratrooper during World War II. The twilight zone is also used in oceanography to define the transitional area, also known as the mesopelagic or middle zone, between the upper layer of the ocean, which is penetrated by sunlight and the total darkness at the bottom of the ocean.[2]

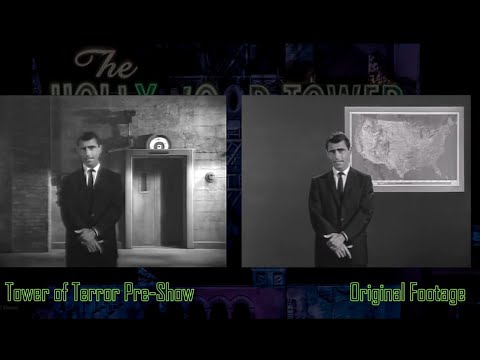

8 Easter Eggs in Walt Disney World’s Tower of Terror

The Imagineering team that designed The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror elevator drop ride in Disney World knew that Serling’s signature introduction had to be included for the preshow film. The problem was that Serling had died many years prior. The solution was to use footage of Serling introducing the episode “The Good Life” but to dub over his voice with an impersonator to explain the ride’s original storyline. Serling’s widow, Carol Serling, picked Mark Silverman for the job herself. There are also numerous replicas from the show scattered throughout the attraction. The broken glasses from “Time Enough at Last” are displayed on a stack of books, the fortune teller machine from “Nick of Time” is on the top shelf in the library, and the creepy ventriloquist dummy from “Caesar and Me” can be seen by guests just before they get off the elevator.[3]

7 One Episode Technically Won an Oscar

By the time the original series of The Twilight Zone hit its fifth season, Serling was running short on ideas, and the budget was running short on cash. Producer William Froug had an idea that helped ease both problems: he bought the rights to Robert Enrico’s short film An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge and aired it as an episode of the show. He paid $25,000 for the film, considerably less than the average episode cost of $65,000. The film was shortened slightly and given the expected introduction and conclusion by Serling but was otherwise untouched. By the time the French film, which features almost no dialogue, aired on American television in 1964, it had already won two awards: Best Short Subject at the 1962 Cannes Film Festival and the 1963 Academy Award for Live Action Short Film. This makes it the only Twilight Zone episode to ever win an Oscar.[4]

6 Rod Serling Was Not the Original Narrator

Serling’s opening and closing narration is a signature part of The Twilight Zone, but he was not originally intended to be the narrator. Westbrook Van Voorhis was hired to do the pilot episode, “Where Is Everybody?” but it was decided that his voice was too pompous. The next choice was Orson Welles, but his fee was too high. “Rod himself made the suggestion that maybe he should do it,” explains producer William Self. “It was received with skepticism. None of us knew Rod except as a writer. But he did a terrific job.” With Serling taking over narration duties, it was decided that he would rerecord the pilot. This was easy to do because, in the first season, the narration was only a voiceover; Serling did not appear onscreen until the second season. Rerecording the narration also gave him the chance to fix the opening line. “There is a sixth dimension beyond that which is known to man” is the line Serling originally wrote, thinking there was a fifth dimension. [5]

5 “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” Inspired “William Shatner’s Seat” on Planes

“Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” is one of the show’s best episodes. It follows Robert Wilson (William Shatner) as he is tormented by a gremlin on the wing of an airplane. Written by I Am Legend (1954) author Richard Matheson and based on his short story of the same name, it has been remade twice, first in Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983) and second in the 2019 reboot. It has also been frequently parodied, most notably in The Simpsons episode “Treehouse of Horror IV,” a segment which sees Bart being tormented by a gremlin on the school bus. As well as having a massive onscreen impact, the Richard Donner-directed episode also had an impact on air travel. Planes have little triangles on the cabin walls, which align with the wings. This is to aid the cabin crew in identifying the best window to look out of during wing inspections. The seats below these triangles are sometimes called “William Shatner’s Seat,” inspired by The Twilight Zone episode. Shatner also starred in the episode “Nick of Time” before bagging the role of Captain Kirk in Star Trek.[6]

4 Only Serling Was Allowed to Use the Word “God” in Scripts

Serling wrote or co-wrote 92 of the show’s original 156 episodes, relying on writers such as Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont, and George Clayton Johnson to write the rest. Before he turned to professional writers to help write the show, he first put out an open call for teleplays. He received 14,000 submissions in just five days, all of which were either rejected or unread. Other notable writers that Serling brought in include The Waltons creator Earl Hamner Jr. and sci-fi writer Ray Bradbury. However, Serling had a lot more freedom when it came to writing episodes. There was apparently a rule which prevented anyone but Serling from using the word “God” in scripts, although the reason why remains a mystery. “I used to get ticked off at Rod because he could put ‘God’ in all his scripts,” Matheson remembers. “If I did it, they’d cross it out.”[7]

3 A Helicopter Crash Killed Three Actors While Filming Twilight Zone: The Movie

On July 23, 1982, filming was nearly finished for John Landis’s segment of Twilight Zone: The Movie when tragedy struck. Lead actor Vic Morrow and child actors Renee Shin-Yi Chen and Myca Dinh Le, who were 6 and 7 respectively, were killed by a helicopter stunt that went wrong. Morrow’s character was heroically saving the children from the attacking helicopter when the pyrotechnic explosions caused the chopper to crash into the trio. The storyline with the children was cut from the film, but the rest of Morrow’s scenes were included. Watch this video on YouTube Landis, along with associate producer George Folsey Jr., pilot Dorcey Wingo, production manager Dan Allingham, and explosives specialist Paul Stewart, was tried for involuntary manslaughter but were found innocent, despite clear issues onset. Landis and Folsey failed to get legal waivers for the children to work at night and around explosives, and concerns raised by a fire-safety officer about the explosives interfering with the helicopter never reached the filmmakers. Although accidents are sometimes unavoidable, this tragedy prompted the industry to improve its safety standards. The Injury and Illness Prevention Program was introduced, insurance was more heavily used (which necessitated stricter rule-following), and risk managers were brought in.[8]

2 George Takei Starred in an Episode That Was Pulled from Syndication

There are a number of Twilight Zone episodes that were pulled from syndication after their first airing, usually because they were tied up in lawsuits over copyright claims. “A Short Drink from a Certain Fountain,” “Sounds and Silences,” and “Miniature” fall into this bracket. However, “The Encounter,” which first aired in 1964, was pulled for entirely different reasons. The episode revolves around an interaction between a Japanese American man (played by a pre-Star Trek George Takei) and an American WWII veteran (Neville Brand). While “The Encounter” attempts to deal with the complexities of race in America, it ultimately perpetuated harmful stereotypes. Takei reflects that it was controversial with “Japanese American and Asian America civil liberties groups and advocacy groups and so for that reason, CBS pulled that episode.” It was decades before it was aired again on American TV. “I missed out on my residuals from that one,” Takei jokes. As well as being back in syndication now, it is also available on DVD and streaming services. Takei also had a small role in the episode “You Might Also Like” from 2020.[9]

1 “Where Is Everybody?” Was the Third Pilot Episode

Serling’s first pilot for The Twilight Zone was revised from a script that he’d written for his anthology show The Storm, which aired on a local TV station in Cincinnati in 1951. “The Time Element” has all the hallmarks of a Twilight Zone episode, from its sci-fi premise about a man going back in time and trying to stop the attack on Pearl Harbor to its twist ending. In 1958 CBS bought the script but then shelved it until they sold it later that year to the anthology show Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse. “The Time Element” provoked an overwhelmingly positive response, prompting CBS to finally take a chance on The Twilight Zone. Serling had to write a new pilot, though, and penned “The Happy Place,” which was about a society that executes people at the age of 60 for being obsolete. Producer William Self liked the story but thought it was too dark for a pilot. Serling finally got the green light with the episode “Where Is Everybody?” and “The Happy Place” was reworked as “The Obsolete Man” for season 2.[10]