10The Thief

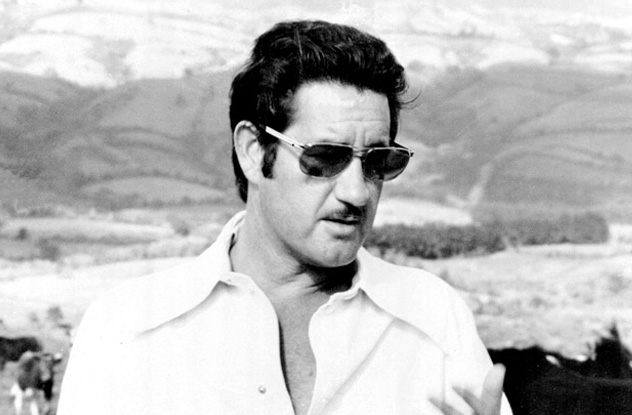

Robert Vesco grew up in Detroit, where his dad worked on the Chrysler assembly line. He could have had a good job in the auto industry himself, but even as a teenager he had three goals: “To get the hell out of Detroit, be president of a corporation, and become a millionaire.” As an adult, Vesco became an itinerant salesman, hustling everything from aluminum sidings to awnings. He eventually came across a small valve-making company that desperately needed $125,000 to avoid bankruptcy. In return for control of the company, Vesco promised to find the money. Vesco rolled into New York and began approaching potential investors. Although he was broke, he represented himself as a successful consultant, dressed in nice suits, and drove a leased luxury car. He got the investment. Still in his early twenties, Vesco was out of Detroit and president of a corporation. A few years later, Forbes ranked him one of the richest Americans. The article simply listed his occupation as “thief.”

9The Scam

Once he took control of the valve maker, Vesco started perfecting his scam. By misrepresenting his assets, he was able to obtain loans to purchase larger companies. Then, he would sell or loot the assets of those companies to repay the loans. He bought companies using their own money. An associate explained how Vesco took control of one plant: “He had the machinery appraised, took the appraisal to a leasing company, and borrowed money on it. Paying the company’s debts, he issued preferred stock in the same company and gave it to the owner as payment. Thing is, the owner could have done the same himself.” This was a high stakes game, and only a talented confidence man like Vesco could have pulled it off. He was an amazing salesman and had a talent for charming investors. There were rumors that he invested Mafia money. But the mergers kept coming, and Vesco’s ambitions continued to swell.

8The Operation Grows

In 1965, Vesco decided to take his company public. But he knew it would never survive the financial scrutiny required to get listed on the stock exchange. So he bought a failed company called Cryogenics, which was already listed. He then transferred all his assets to Cryogenics and changed its name to the International Controls Corporation (ICC). Even though the company was nothing like Cryogenics, it was able to keep the stock market listing. Vesco promised huge returns and gained a reputation as whiz kid. ICC stock was soon worth millions—-even though its net income was only $229,000. It got bigger. In 1967, Vesco acquired a company called Electronic Specialty (ES), even though it had sales of $112 million and ICC only had sales of $6.8 million. Vesco told ES shareholders that Bank of America was backing the deal. In reality, the bank had only agreed to underwrite part of it, but Vesco was easily able to secure further backing once he controlled ES’s assets.

7The Target

Vesco knew his house of cards would collapse eventually. So he started looking around for one last big score. In 1970, he found it: Investors Overseas Services (IOS) Founded by flamboyant financier Bernard Cornfeld, IOS operated several mutual funds popular with small investors and soon became a runaway success. IOS particularly targeted those looking to avoid tax and was registered in Switzerland to avoid government scrutiny. Cornfeld was a good salesman but a poor manager, and a bad year in 1969 sparked investor fury. To make matters worse, IOS only took a commission if its funds made a profit. When they made a loss in 1969, the company found itself almost out of operating cash. Cornfeld, who was awkwardly aware that many of IOS’s activities skirted the law, felt trapped (he later served 11 months in a Swiss prison). Vesco swooped in. He offered $5 million to resolve the cash problem. The investors decided that Vesco was a better bet than Cornfeld and agreed to give him control. For $5 million, Vesco acquired a company that managed $700 million.

6The Heist

As soon as Vesco had control of IOS, he began one of the greatest heists in corporate history. His key asset was IOS’s emphasis on secrecy. This was supposed to protect tax-avoiding customers (investors used to show up with suitcases of cash). But it also meant there was almost no oversight. Vesco could do what he liked. After staffing IOS with his loyalists, Vesco began cashing out the company’s biggest investments. The money was then “invested” in companies in various tax havens around the world. In reality, these were shell companies set up by Vesco. They had no products or employees. They only existed on paper. The shell companies then took the money and “lent” it to other shell companies, which “invested” in further shells. After filtering through a dozen countries, the money was untraceable. In this way, Vesco stole at least $224 million dollars, equivalent to over $1 billion in today’s money. It was enough to make him one of the richest men in the world.

5The Investigation

With the money he stole, Vesco bought a private Boeing 707, complete with a sauna and a disco. The plane was named “Silver Phyllis” after a syphilis outbreak among the call girls who doubled as stewardesses. A $1.3-million-dollar yacht was the icing on the cake. Meanwhile, Vesco continued to live a double life as the toast of Wall Street, the whiz kid who had saved IOS from collapse. But even as he partied in the air, investigators were closing in. In 1972, the Securities And Exchange Commission (SEC) filed charges against Vesco, alleging that he had looted at least $224 million. But Vesco had been monitoring the SEC investigation closely. Shortly before the charges were filed, he fled the US on a commercial flight. He paid hundreds of dollars in excess baggage fees, and it has always been rumored that his suitcases were stuffed with millions in cash.

4Funding Watergate

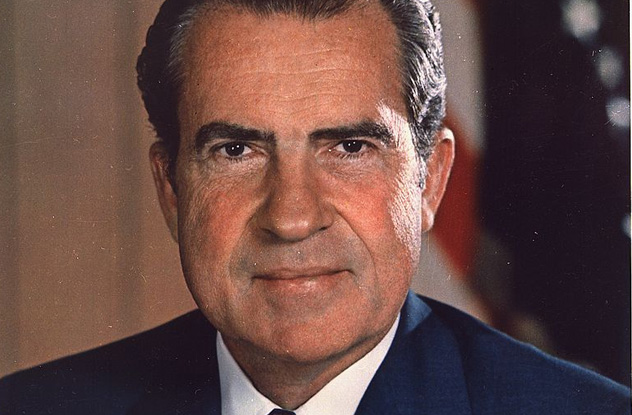

Shortly before fleeing the country, Vesco tried one last roll of the dice to get the SEC off his back. President Richard Nixon had set up a secret unit known as “the Plumbers,” which carried out illegal operations on his behalf during the 1972 election. It was the Plumbers who broke into the Watergate Hotel, triggering the scandal that brought Nixon down. Nixon couldn’t put the Plumbers on the government payroll. And since campaign donations were closely monitored, he couldn’t pay them with those either. So the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP) began soliciting illegal cash donations that could be kept “off the books.” In 1972, Vesco met with Commerce Secretary Maurice Stans and agreed to hand over a briefcase containing $200,000 in cash (equivalent to about $1 million today), which was used to finance the Watergate burglary and the cover-up that followed. In return, Nixon officials agreed to put pressure on the SEC.

3The Fugitive

But the SEC couldn’t be bought, and Vesco had to flee—-in a recording, Nixon can be heard insisting that the donation wasn’t a bribe because “ICC didn’t get anything! We indicted them!” Later in the recording, Nixon is told that Vesco “will go to Costa Rica, where he’s bought the president.” Nixon’s response involves calling the Italian-American Vesco “a cheap kike.” Sure enough, Vesco did turn up in Costa Rica, where he had promised to invest $42 million. Before long, he was living in a palatial compound and the government of Costa Rica had passed a law specifically banning his extradition. For the next 20 years, Vesco cruised around Central America and the Caribbean. As soon as the pressure on one country to extradite him grew too great, he moved on to another. From Costa Rica, he went to the Bahamas, where he sponsored the ruling PLP. He later appeared in Antigua, ruled by the notoriously corrupt Bird family. His stolen wealth made him untouchable.

2The Overseas Crime Spree

In his exile, Vesco continued his crime spree and enjoyed thumbing his nose at the US. He dodged an FBI plan to kidnap him at a Bahamian airport. When the government impounded his yacht, he sent someone to Florida to steal it back. He told the government of Libya he could do the same for eight transport planes seized by the Carter administration (the Libyans balked at his $30 million fee). In the Bahamas, he lived next to Medellin Cartel boss Carlos Lehder and became involved in cocaine and weapons trafficking. He was obsessed with the idea of founding his own country, a tax haven where white-collar criminals would be welcome. After an attempt in the Azores fell through, he tried to buy the island of Barbuda for the “Sovereign Order Of Aragon,” a center for money-laundering and drug trafficking. As an associate put it, Vesco “hurt, denigrated, or corrupted everyone he had contact with.”

1Curing Cancer

By 1982, Vesco was running out of places to hide. But friends in Nicaragua arranged for him to move to Cuba, where he allegedly paid $50,000 a week for Castro’s protection. He also met up with an old friend—-Richard Nixon’s nephew Donald. Vesco and Nixon teamed up to promote a drug called Trioxidal, which they claimed could cure cancer, AIDS, and the cold. It was also going to allow people to live for centuries. A Cuban health service lab run by Fidel Castro’s nephew was lined up to manufacture the miracle pills. Fidel himself was less impressed, and Vesco was soon arrested for fraud. By that point, he had apparently run out of money for bribes. There were also rumors that he knew too much about Cuban drug smuggling and the arrest was partly to keep him quiet. After spending a decade in prison, he lived quietly in Havana until his death from cancer in 2007. Evidently the Trioxidal didn’t work.