10 Leaders Were Chosen At Random

The government of Athens was run by a council of 500 men called the Boule. While every citizen played a role in turning the great wheel of democracy, the Boule were especially important. They ran the day-to-day affairs of the government, decided what decrees would be voted on, and played a very major role in leading the country. The Greeks didn’t get to vote for their council, though. They drew lots, randomly choosing 50 men from each of the ten tribes of Athens, simply based on who drew the shortest straw. The head of the Boule, too, was chosen by a random draw. That person was in charge of the money, the state documents, and the state seal—and he was picked by a completely random lottery. As weird as it sounds, there were actually some major advantages to this. Voting, the Greeks believed, led to only a select few power-hungry people being in charge. With their system, people with no interest in politics ended up in council. Socrates, for example, insisted he was never politically active, “except for being once on the council,” a job he saw as irrelevant to his life.

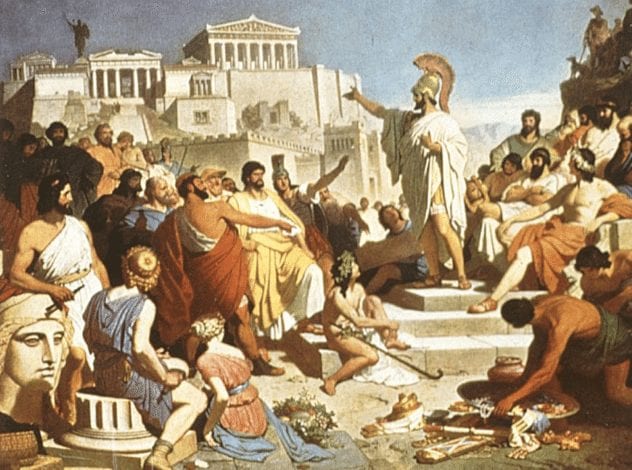

9 Every Eligible Voter Could Vote On Everything

The Boule didn’t make the decisions; everyone did. Every ten days, every single citizen of Athens would be invited to a large, theater-shaped arena near the Acropolis, where they would vote on every decision the country made. They voted on everything, from details of festivals to foreign policy and wars. And anyone could talk about anything. They would ask, “Who wishes to address the assembly?” and every person present would be free to contribute. Of course, that didn’t mean their opinion had to be respected. If a baker started talking about the best way to build ships, he’d be laughed and jeered at until he either sat down or was kicked out. Just because everyone was invited didn’t mean everyone came. It was rare to get more than 6,000 of the 40,000 eligible people to show up—and they didn’t even expect it. In the early years, the place they met only had room for 5,000 people.

8 Only 10–20 Percent Of The Population Could Vote

“Citizen” didn’t mean everyone in Athens. In a population of 260,000, there would be 150,000 slaves and 10,000 foreign-born residents who didn’t have the right to vote. Of the remaining 100,000 people, only men aged 18 and older could vote, which meant that out of a quarter of a million people, only 40,000 could vote. There were, apparently, some circumstances when everyone got to vote. There are records suggesting that some foreigners and slaves were given the right to vote, although the details are unclear. Most of the time, though, decisions were made by 40,000 free men—or, more accurately, the ones who bothered to show up. On average, only about 3,000 would actually show up to have their voices heard.

7 They Had To Herd People In To Get Them To Vote

Voting wasn’t always voluntary. As time went on, people became less and less interested in voting on every single decision, and they stopped showing up. The Greeks didn’t just let them stay home, though. They did something about it. First, they started paying people to show up to sessions. When that didn’t have enough an impact, they forced them. They would close down every market and shut off every road in Athens that didn’t lead to the assembly. Then, a group of slaves would circle around the population carrying a rope soaked in red ocher and slowly close in on them. The people were forced to run to the assembly as quickly as they could. Any who didn’t get there fast enough and was caught with red paint on their clothes would be fined for skipping out on their civic duty.

6 Courts Had A Jury Of 500 Peers

As frustrating as jury duty might be today, our court cases only require a group of 12 people. When the Greeks went to court, they called in a jury of 500 peers, which meant that every time a jury was formed, an eligible voter had more than a one percent chance of being called. They used juries a lot, too. Minor offenses could be dealt with by officials, but anything that involved a more severe penalty than a 50 drakhmai fine required a jury. The juries could make major decisions. Political cases frequently came up to these courts of public opinion, and the careers of major figures would end in front of them. Even Socrates reached his end in front of a jury of 500 Athenian citizens, who ruled for his death.

5 They Only Taxed The Wealthy

The Greeks didn’t believe that citizens should be required to pay taxes. Under normal conditions, the people of Greece didn’t have to pay a dime to the state. Instead, the government got its money from customs duties and taxes on foreign residents—and from the wealthy. Only the very richest people in Athens were required to pay taxes. At first, they relied on funding from the top 1,200 wealthiest people, but in time, even that number was lowered down to 300. Instead of complaining, the wealthy would actually volunteer to pay more. Being taxed was a social status symbol in Greece, so men would offer to give more money to the government toward military or cultural spending, just to show off how rich they were.

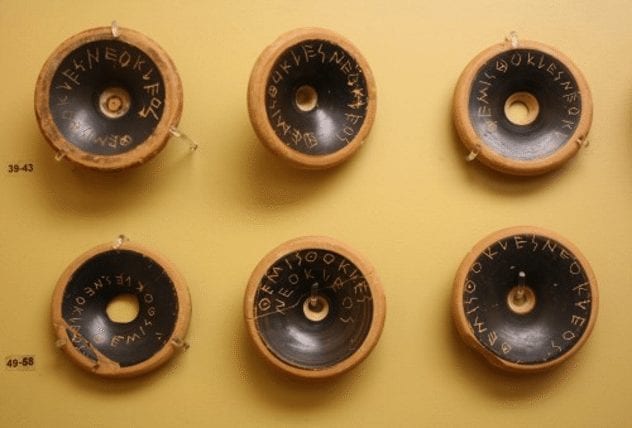

4 You Could Vote To Exile Anyone For 10 Years

Once every year, the citizens of Athens would gather together and get the chance to kick one person out of the city. They would start by voting on whether or not to exile anyone that year. If the yeas had it, someone was going to leave. Everyone would be given a piece of pottery and would have to write the name of one person they thought should be exiled on it. The votes would be tallied, and as long as there were at least 6,000 votes cast, they would kick the person who got the most votes out of the city. The purpose was to keep people from becoming too powerful. Technically, though, you could vote for anybody for any reason. You could exile the guy next to you for breathing too hard—and some people tried to do just that. At least one person admitted that he voted to exile Aristides because he thought the nickname “Aristides the Just” was a bit pompous.

3 You Could Try To Get Anyone Banned From Politics

Before anyone entered office, they would be scrutinized for their worthiness. Every part of their lives would be tested, and they could lose their position for any reason, from debt to squandering inheritance. Even their families would be on trial. They would be asked if they had shrines to Zeus in their homes. They would be asked how they treat their parents, where their families’ tombs were, and how often they visited those tombs. If you didn’t like somebody, though, you could make them go through that trial any time you wanted. They would make you stand in front of them as their accuser, but you could force the state to scrutinize any citizen at any time—and, if they lost, they would lose their right to vote.

2 It Was Still Horribly Corrupt

To some, Athenian democracy might sound like a flawless paradise, but it wasn’t. Just like our systems today, it was rampant with corruption and flaws. Though the Boule was supposed to be chosen at random, the numbers don’t add up that way. A disproportionately large number of wealthy, influential people ended up in power. Those wealthy people dominated decision-making, too. The Greeks tried to make every citizen literate, but they failed, and only an estimated five to ten percent of people could read or write. Most were horribly ill-informed and easily swayed by strong speakers, so it was said that a group of 100 men swayed the minds of the other 40,000. Ostracism, too, seems to have been corrupted. Archaeologists have unearthed a stack of ballots with the name “Themistocles” etched on them—all in the exact same handwriting. Apparently, somebody tried the rig the vote. In the end, Greek democracy didn’t last. Two centuries of voting went by before the nation gave up on the rule of the people.

1 Spartans Made Decisions By Shouting

Of course, Athens was just one part of Greece. Over in Sparta, they were making decisions the Spartan way—by going with whoever could shout the loudest. Sparta was governed by a group called the Ephorate, who were elected for terms of a single year. They were below the king, but some have called them “the real rulers of Sparta.” When they wanted to choose their leaders, though, they didn’t cast ballots. They just said a name, let the people shout, and went with whoever had the loudest supporters. The Athenians weren’t impressed. Aristotle dismissed Spartan elections as “childish.” Perhaps their version of democracy, though, has outlived the Athenians’. Read More: Wordpress