President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942. His go-ahead allowed more than 100,000 Japanese Americans to be uprooted and relocated to isolated, high-security internment camps. Pressure to sign came from military officials, politicians seeking favor among the American majority, a hysterical public, and even greedy farmers who were anxious to purge their competition. It worked.

10Home Raids

Soon after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, FBI agents raided homes of the Issei (i.e., first-generation immigrants from Japan). The American government also froze the assets of anyone connected to Japan. These actions violated people’s rights to their property, invaded people’s privacy, and resulted in the arrest of 1,212 innocent Issei—and this was just the initial round-up. Irreplaceable family heirlooms were confiscated, never to be returned. Potentially dangerous items and objects with a special connection to Japan were labeled “contraband.” Possession of contraband was illegal because it showed allegiance to the enemy. Anyone caught holding on to their precious family keepsakes was arrested. Targets included first-generation immigrants and Japanese-American citizens—farmers, teachers, business owners, doctors, bankers, and various other productive members of society. Many had already had their assets frozen on July 26, 1941, in response to a Japanese invasion in Asia months before the Pearl Harbor bombings. These freezes, forcible seizures of property, and undeserved arrests were only the beginning of injustices experienced by loyal Japanese Americans.

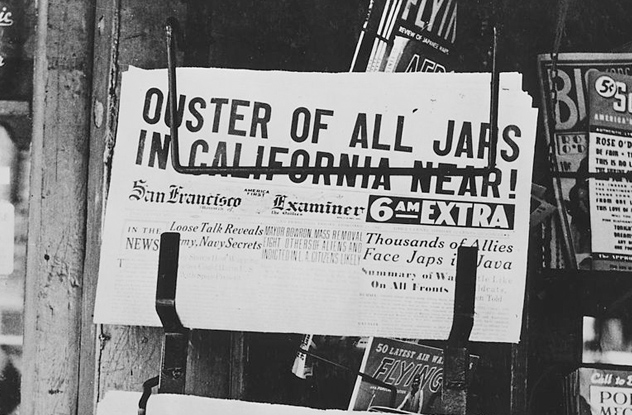

9Forced Evacuation

Registration was the first step to evacuation. After registering, Japanese Americans were expected to follow strict rules, such as curfew and travel restrictions. They were eventually ordered to abandon home. Those whose assets weren’t frozen weren’t given long to sell their businesses and property. Belongings were let go at a fraction of their worth, if they could be sold at all. Some Japanese Americans avoided this fate by moving farther east. Approximately 150,000 Hawaiians also avoided internment. Almost 40 percent of Hawaiian islanders were Japanese-American. Though the racial connection caused fear, powerful Hawaiians demanded that those of Japanese ancestry be left alone. Many labored on the pineapple and sugar plantations, and they were essential to local economic success. The population of the west coast received no such protection, and they suffered immensely for it.

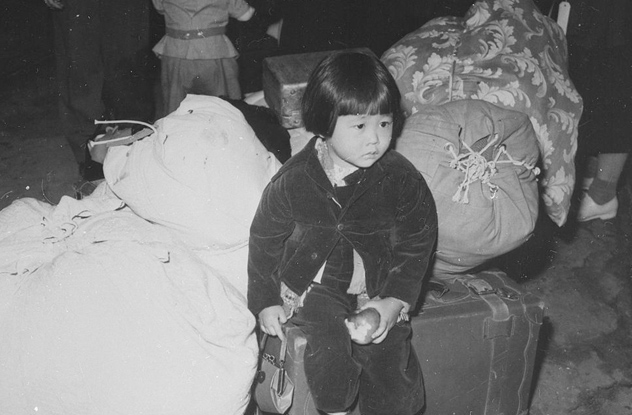

8Assembly Centers Built For Animals

When evacuated, Japanese Americans were only allowed to take what they could carry. Each internee was sent to one of 16 assembly centers. From there, they were assigned to one of 10 internment camps. The most well-known is Manzanar War Relocation Center. Racetracks and fairgrounds were the types of environments used for the assembly centers. Internees stayed in animal stables and stalls where livestock had been kept recently. The stench of manure rose up from the ground, dust blew inside, and people were forced to literally live like animals. Many of these units didn’t even have roofs overhead. Health care, food, and general cleanliness were disgustingly low-quality.

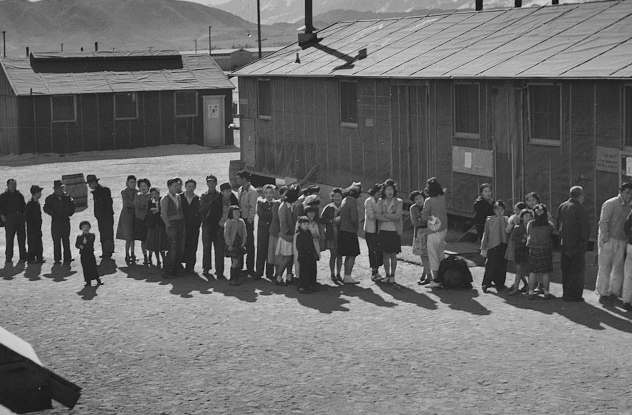

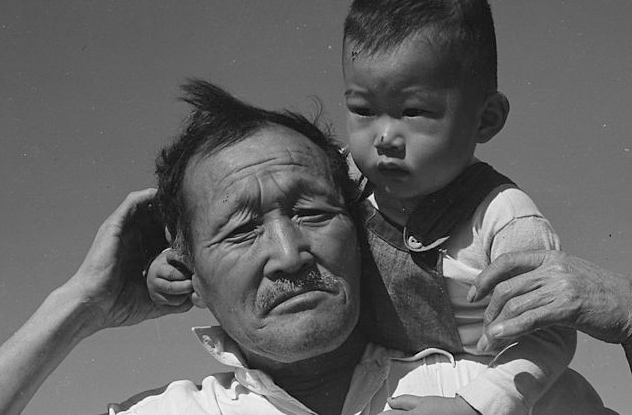

7Communal Living

The treatment of interned Japanese Americans was similar to that of European POWs. Sometimes, family members would be sent to separate barracks, and sometimes they’d be sent to separate camps. Internees were forced to share living quarters with strangers. They could not even get dressed in privacy. Since the barracks didn’t include toilets, everyone had to wait in line to use communal latrines, which did not include partitions. Showers were taken in open areas, meant to service many people at once, rather than to accommodate modesty. Even running water had to be acquired from a communal source. Living in close quarters and sharing so much, on top of the terrible housing conditions, gave easy rise to sickness. Proper medical care was rarely accessible. Numerous people died or experienced great suffering for lack of the necessary medical treatment. The physical and emotional trauma from internment became a permanent part of the people’s lives.

6The All-Japanese Regiment

Not even World War I veterans, who’d fought courageously and honorably for the American cause, could avoid being interned. They were pigeonholed as enemy aliens. One way to escape the camps, however, was to enlist in the 442nd Infantry Regimental Combat Team. Everyone in the regiment was Japanese-American. Many who enlisted saw it as an opportunity to prove their loyalty to America. Internees were classified as 4-C, or enemy aliens, whereas soldiers were seen as allegiant to America. Some camps protested the enlistment of their internees, believing that the 442nd would be sent only on the most dangerous missions. The military still found all the volunteers it needed. Soldiers of the 442nd showed unbelievable bravery and are highly renowned to this day. During the war, 650 of them died. Twenty in the regiment received the Medal of Honor—in the year 2000.

5Desert Prisons

Most of the assembly centers and camps were built on barren land. Internees tried growing crops in the desert, as the government wanted the camps to support themselves, but it didn’t always work. The interned Japanese Americans were paid low wages for their labor. In the summer, desert heat sent the temperature above 38 degrees Celsius (100 °F), and winter temperatures plummeted below freezing. People who’d done nothing wrong were kept behind barbed-wire fences, in desolate camps patrolled by military police. Armed guards kept constant watch and shot anyone suspected of attempting escape. “Troublemakers” were separated from their families and sent to more unpredictable environments. The government paid little attention to the grievances of Japanese Americans. Allegedly, one of the reasons for internment was to protect the inmates from an American public hostile and violent toward the Japanese. But one internee, famously illustrating how it felt to be forced into these camps, posed the question: “If we were put there for our protection, why were the guns at the guard towers pointed inward, instead of outward?”

4Death As Punishment

Attempting escape, resisting orders, and treason were all punishable by death in internment camps. Guards would face little consequence for killing without just cause. A mentally ill man in his mid-forties, Ichiro Shimoda, was shot trying to escape in 1942. He’d attempted suicide twice since entering the camp, and the guards were well aware of his mental illness. That same year, two Californians were killed during an alleged escape attempt from the Lourdsburg, New Mexico camp. It was later revealed that Hirota Isomura and Toshiro Kobata were both extremely weak upon arrival—too weak to walk, much less escape. A handful of guards went to court for their wrongdoings but with disappointing results. One guard was tried for the 1943 murder of an elderly chef named James Hatsuki Wakasa. He was found not guilty. Private Bernard Goe was also tried after killing Shoichi James Okamoto. Goe was acquitted and fined for unauthorized use of government property. The amount: $1—the cost of the bullet used to kill the victim.

3Expatriation

After World War II ended and the internment camps closed, 4,724 Japanese Americans were permanently relocated to Japan. The majority were US citizens or resident aliens. Nearly all of the expatriated citizens were 20 years old or younger. Teachers in the internment camps had taught them how to read and write Japanese and to be proud of their heritage so they’d have an easier time assimilating. They were transported directly from the internment camps to ships and then overseas to their new homeland of Japan. More than 20,000 Japanese Americans requested to expatriate between 1941 and 1945. The longer that internment continued, the more requests were filed. Asking to leave the US was a form of nonviolent protest. Those who requested expatriation weren’t forced to follow through once internment was over. However, we’ll never know what the thousands relocated to Japan might have contributed to American society had they remained.

2Rebranding

Today, we call them”internment camps.” A more accurate term would be “concentration camps.” They were called exactly that by then-President Roosevelt as he confidently endorsed them. The name “enemy alien internment camps” was also used to describe these centers. The modern wording stems from how they weren’t the vicious death camps experienced in Europe, which is how most people view concentration camps today. Internees enjoyed weddings, gardening, painting, sports, clubs, and even newspapers. There were no gas chambers. Inmates were not doomed to genocide. Still, “internment camp” doesn’t do justice to the horrors experienced within them. Japanese Americans were uprooted from their homes and treated like criminals. They experienced enormous loss. They suffered great physical and emotional trauma. A racial minority was concentrated in specific areas for the security of the nation, imprisoned in deplorable conditions, and stripped of their dignity. They were living in concentration camps.

1Lack Of Remorse

Anti-Japanese sentiment remained even after the last camp closed in March 1946. Former internees who returned home for their assets were beaten and even killed. Neighborhood signs declared that “Japs” weren’t welcome anymore, warning them to keep away. Not only did they lose their belongings, they lost their sense of belonging. They weren’t even welcome to rebuild the lives they once knew. Worsening the matter, the American government was slow to admit its mistake. Fred Korematsu challenged the legality of Executive Order 9066 in 1944. He lost in the Supreme Court by a 6–3 vote; internment was rationalized as a wartime necessity. A formal US apology and recompense was finally offered through the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. Former inmates became eligible for a one-time restitution payment of $20,000. Many of their losses greatly exceeded that value. There’s no way to truly make up for the way Japanese Americans were treated during the World War II era, but we can be more considerate of the rights of all Americans in the future. Shannon M. Harris is a writer from the Seattle area. She enjoys watching stand-up comedy, visiting quirky roadside attractions, and exploring nature—as long as nature isn’t trying to kill her. Connect with (and hire) her at WriterBug.org.