10 Egyptian Animals

The ancient Egyptians were keen naturalists and tedious archivists, allowing modern researchers to piece together the region’s ecology as it flourished 6,000 years ago. Animal iconography was a common motif, and the assortment of local beasts was preserved through a variety of media, including carvings, rock art, ceremonial pieces, and murals on tomb walls. Combined, these sources provide a thorough record of Egyptian fauna and a depressing reminder that of the 37 large mammal species that once roamed the Earth, only eight remain. The picture was strikingly different in the pre-Christ era: Egypt mirrored a North African Serengeti, inhabited by all manner of savanna dwellers, including lions, wildebeests, zebras, and wild dogs. Sadly, a good number of these creatures were lost during periods of drought, although human competition and loss of habitat are also to blame. With many elements of an ecosystem codependent, the process is accelerated as each new species is returned to dust. For example, every herbivore that dies off provides one less food source for predators. Researchers warn that the few survivors are at greater risk now than at virtually any time since the end of the last ice age.

9 The Downfall Of Cahokia

About 1,000 years ago, Cahokia was North America’s greatest city, composed of 120 mounds spread out over 15 square kilometers (6 mi2) of the mighty Mississippi-adjacent floodplain. At one point, the city boasted a population of 20,000, larger than that of London and other prominent European centers. Some estimates place an even more impressive 40,000 inhabitants within its ancient city limits. The settlement flourished until about 600–700 years ago when its population—already in decline and reeling from the political struggles inherent to all civilizations—was apparently decimated by some mysterious natural disaster. Now it appears that a series of megafloods was to blame. The discovery was somewhat accidental. Researchers were dredging up sediment from Horseshoe Lake near the city’s epicenter. They were in search of fossilized remains, artifacts, and pollen to gauge the extent of human activity at Cahokia. Instead, they found evidence for numerous past flooding events, which regularly occurred before Cahokia was founded. The floods took a hiatus and then returned with a vengeance around the time that the population declined. Therefore, the city’s great riparian lifeline, which ensured its existence, guaranteed its downfall as well.

8 Mysterious Cave Mural

Archaeologists working at a Neolithic hot spot near the Turkish city of Konya were baffled by a cave mural depicting what appears to be an extensive collection of Etch A Sketches enshrined beneath a leopard-skin rug. Initially discovered during previous excavations in the 1960s, researchers had not been able to agree on the interpretation of the mural. Some considered it the world’s oldest map, showing the ancient community at Catalhoyuk during its apogee around 9,000 years ago. Others chalked it up to crazy, prehistoric abstractions—unknowable themes dreamed up by artists who are long gone. Researchers now believe they’ve cracked the conundrum: The mural records a past volcanic eruption. The cells represent the settlement viewed from above, the odd spotted object is nearby Mount Hassan, and the formerly unintelligible lines branching therefrom are flows of magma and pillars of smoke. Supporting that hypothesis, the mound pictured in the mural has two humps of similar size like those on Mount Hassan, which are known as Small and Big Mount Hassan. Furthermore, pieces of pumice (ejected volcanic rocks) found within the area suggest that an eruption occurred about 8,900 years ago when Catalhoyuk was thriving.

7 The Honeycombed Skull

In 1480, the Italian city Otranto was invaded by Ottoman forces, who ransacked the town and murdered most of the adult men. The remaining 800 men were asked to renounce their Christian faith. After they refused, they were marched out of town and summarily beheaded. Most women and adolescents were also slaughtered, with the rest pawned off into slavery. In 1771, the abstainers were beatified as the “martyrs of Otranto” and are now honored as patron saints of that besieged city. Several centuries later, the skulls belonging to the recently canonized (circa 2013) martyrs are now on display in the Cathedral of Otranto. But strangely enough, someone drilled 16 holes into one of the skulls. Thankfully, it appears that the precisely bored holes were added long after death to harvest skull residue. Bone powder was once a favored remedy for sundry ills, and we can only imagine that this holy bone powder was considered ne plus ultra. Indeed, the tools used for the procedure appear to be of a type specifically designed to obtain powder by pulverizing bone matter.

6 The Mysteriously Unwieldy Coins

Anthropologists discovered an ancient world anachronism when they unburied a horde of awkwardly shaped coins at an excavation site in Ziyaret Tepe, Turkey. With shapes from pyramids to wizards’ hats, the clay coins served as markers of trades that had gone down in the ancient city of Tushan. These devices were standard before the advent of written text. But from 3000 BC onward, they faded from history. Yet the recently discovered stockpile in Turkey dates back to around 1000 BC, when cuneiform writing was in full swing. Despite the chips’ assumed obsolescence, it seems that people still exchanged them instead of just recording transactions textually. The tokens were cleverly used in an empire-wide system of administration to catalog the sizable Neo-Assyrian nation’s many goods and resources. As many farmers, herdsmen, and other laborers were still untrained in the written word, coins offered the most efficient way to keep track of livestock. These numbers were then tabulated on cuneiform tablets by literate city officials who recorded the scores of products entering city gates.

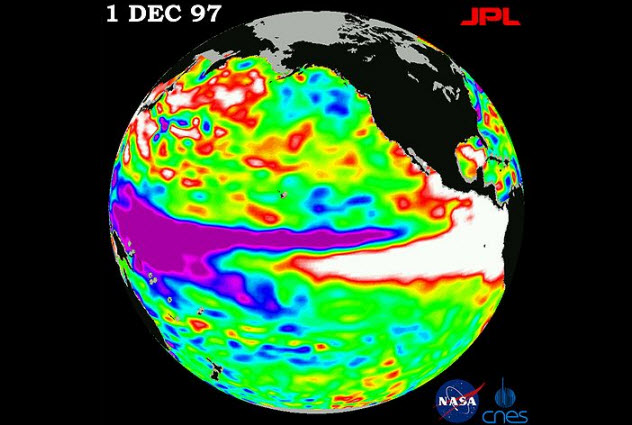

5 Seashells And El Nino

The El Nino cycle is the most influential agent in short-term, year-by-year climate change. Until recently, researchers thought they had accurately mapped out its past transgressions. However, an unassuming cache of seashells shows that past cycles were similar to those we have today and suggests a new degree of unpredictability for those to come. El Nino occurs when winds that normally push warm waters east across the equatorial Pacific cease or change direction, allowing increases in average sea temperature. These semi-irregular changes eventually reverse and sometimes drive sea temperatures below average values in a process known as La Nina—thus completing one revolution of the El Nino Southern Oscillation event. Researchers can somewhat predict these capricious winds, so our climate models assumed that El Nino was much weaker in the past, especially 10,000 years ago. When analyzing gigantic mounds of shells that were discarded by indigenous people in what is now Peru, researchers teased out a thorough climatic record by calculating oxygen ratios within the shells. Unfortunately, the El Nino patterns of the past did not match up with the scientific models that attempted to explain its fluctuations. Previously, it seemed as if Earth’s bobbling through space was the culprit, with the varying levels of solar radiation affecting the strength of the events. Yet the shells discourage the effects of solar input, suggesting that other factors like huge ice and water dumps from melting glaciers have been severely underestimated.

4 Stonehenge Stones Suggest A Previous Monument

As the much-studied yet still mysterious Stonehenge continues to divulge its mysteries, the learned men responsible for such things pinpointed that the bluestone slabs originated at an ancient worksite in Preseli Hills, Pembrokeshire, Wales. Stonehenge is made up primarily of two types of stone. The large, freestanding chunks are a local sandstone called sarsen. The other bits, the aforementioned bluestone, are forged by volcanic processes and come in two flavors: rhyolite and “spotted” dolerite. Dating suggests that they were established some 400 years before the beefier megaliths. Thanks to a quirk of local geology and a gloomy Welsh climate, the bluestones occurred naturally as pillars, and manual excavation required little work other than jamming wooden stakes between the columns and waiting for rain. Exposed to a downpour, the stakes absorbed water, expanded, and snapped the preshaped stones from the craggy face of the cliff. After dating the excavations to around 3300 BC, researchers now believe that a Stonehenge Lite was first erected somewhere near the quarry site in Wales. The team is confident that they’ve found its former home and hope to confirm the theory in 2016.

3 Jotunvillur Code

Crypto-anthropologists have just cracked a Viking code from the late Middle Ages that remained tantalizingly unsolved for many years. This happened thanks to a miniature Rosetta Stone, a simple engraving on which two individuals recorded their names in both coded and basic runic. Salivating at the prospect of deciphering the meticulously guarded secret or at least some scandalous gossip, researchers instead stumbled upon an 800-year-old jest: The message read “kiss me.” Apparently, coded writing was used quite differently in the past—for education and enjoyment rather than overt secrecy. Some tricksters even made a game of it, creating runes that boastfully challenged others to “interpret me if you can.” This was especially tough for the jotunvillur code, which by its nature renders messages completely ambiguous. The desired characters (runes) are swapped for the last sound in their name. For example, maor (or “m”) becomes “r.” Overall, the jotunvillur code reveals nothing critically important, just an amusing peek at some unexpectedly playful Viking antics.

2 Fabled Stronghold Acra

Archaeologists have giddily announced the recovery of what they hope to be the fabled Acra stronghold, founded two millennia ago by Greek ruler Antiochus Epiphanes and prominently described in the Book of Maccabees as well as by historian Josephus Flavius. Both sources placed the stronghold within the City of David, leading to failed expeditions and much frustration over the past century. Instead, Acra sits outside the city walls on a hill, strategically overlooking the populated valley below and controlling all traffic to the Temple on Temple Mount. Of course, it had since been plastered over by time and only reappeared after 10 years of scraping away an old parking lot and sifting through layers of earth laid down by the intervening generations. Beneath the accumulated gunk emerged the remnants of a mighty tower, an imposing wall, and a steep outer embankment used as a defensive measure. The discovery is most precious because it has given us a clear picture of the settlement as it stood in 167 BC, on the eve of the famed Maccabean uprising. In addition to the fortress, archaeologists dusted off coins, jugs of wine, and even pieces of weaponry—the same rocks, ballista stones, and arrowheads launched by Hasmoneans during their attempts to conquer the stronghold. It was not until 141 BC that Simon Maccabee, after a lengthy siege, reveled in Acra’s surrender.

1 Roman Concrete

The mystery of how Romans concocted their famous concrete may have finally been solved by Campi Flegrei, an intermittently dormant volcano under the ancient city of Pouzzoli, which was established by Greek adventurers in 600 BC. In 1982, the inferno came back to life, bubbling its way toward the surface. Within just two years, the ground rose 2 meters (6 ft), making the currently shallow pier almost useless, before a procession of small earthquakes forced an evacuation of Pouzzoli’s 40,000 denizens. Yet, curiously, the volcano did not blow historic Pouzzoli sky-high. Examining why this was so, former resident Tiziana Vanorio—now an experimental geophysicist at Stanford—might have inadvertently solved an age-old mystery. Churning beneath the doomed city, a witch’s brew of hot, mineral-rich waters produces calcium hydroxide (aka hydrated lime). The upwardly bubbling lime combined with ash to create a natural concrete that plugged the caldera, averting a volcanic eruption as gases and fluids vented through cracks in the ductile crust. The concrete formed there is so similar to that in Roman constructions that some clever observer must have noticed that the mixture of local ash and earthen sludge yielded this incredibly tough material. Mining volcanic outflows is dangerous business, so the Romans supplied their own lime to make their concrete.