The criminal offenses, which include body-snatching, train robbery, kidnapping, and fraud, involve the use of picks and shovels, dynamite, “burking,” pistols, ropes, knives, water, machine guns, and, yes, even cameras. In addition, each has inspired a cinematic chiller or thriller nearly as terrifying and electrifying as the crime itself.

10 The Body Snatcher & The Flesh and the Fiends

William Burke (1792–1829) and William Hare (d. 1859?) most likely met while working as laborers on the Union Canal in Scotland. The work was hard labor, and they decided to quit. Instead of helping build the canal, they began to supply bodies to Edinburgh’s medical schools, which were always in need of cadavers for dissection during anatomy classes. At first, they dug up graves and stole corpses, but they found that this enterprise was not much easier than the manual labor they had done while working on the canal. They soon hit upon a simpler, easier way of acquiring their stock in trade. Instead of snatching bodies from cemeteries under cover of darkness, they would simply murder people and sell their remains to the medical schools. In doing so, the partners in crime developed an undetectable technique for suffocating their victims. It was called “burking,” after Burke. All went well—until their sixteenth murder—when a witness informed police that a dead body was being stored under Burke’s bed. Burke, his mistress Helen McDougall, Hare, and Hare’s “wife” Margaret were arrested (they were not actually married but lived as man and wife). Fearing there was insufficient evidence to convict the defendants, Lord Advocate Sir William Rae offered Hare immunity from prosecution in return for his testimony against his partner and their accomplices. His wife also received immunity. As a result, Burke was hanged on January 28, 1829. McDougall was released after being acquitted on the grounds of insufficient evidence. Ironically, Burke’s body was donated to a medical school for dissection, and his skeleton remains on display at the University Medical School in Edinburgh. Although Hare’s ultimate fate is uncertain, one source states that he may have died in London, in 1859, as a blind beggar. The Burke and Hare crimes are memorialized in a gruesome snatch of 19th-century verse, which includes a mention of one of their best customers, Dr. Robert Knox: “Up the close and doon the stair,/ But and ben’ wi’ Burke and Hare./Burke’s the butcher, Hare’s the thief,/ Knox the boy that buys the beef.” Their body-snatching and murders also inspired the 1884 short story “The Body Snatcher” by Robert Louis Stevenson, which, in turn, loosely inspired the 1945 movie of the same title, directed by Robert Wise. The movie focuses on an unscrupulous doctor, Toddy MacFarlane (Henry Daniell), and his protege, medical student Donald Fettes (Russell Wade). They are blackmailed by John Gray (Boris Karloff), the body snatcher who supplies their cadavers, into remaining silent after Fettes discovers that Gray has committed murder in order to supply a corpse to them. In the movie, Dr. Knox is not the murderous body-snatcher’s customer, but MacFarlane’s mentor, and, in one of the movie’s scenes, MacFarlane tells the story of Burke and Hare to Joseph (Bela Lugosi), an assistant (and another blackmailer). A number of complications develop, which include additional murders. A later British film, The Flesh and the Fiends (1960)—released in the U.S. as Mania—is also based on the Burke and Hare murders. Directed by John Gilling, it stars Peter Cushing as Robert Knox, Donald Pleasance as William Hare, and George Rose as William Hare.[1]

9 Special Agent

The DeAutremont brothers—twins Roy (1900–1983) and Ray (1900–1984) and Hugh (1904–1959), committed the American West’s last train robbery, the Meriden, Connecticut, Record-Journal notes in a December 22, 1984, article. The brothers, the newspaper explains, “jumped aboard…the Southern Pacific’ Gold Special’ bound for San Francisco as it passed through a remote mountain tunnel near Ashland,” hoping to relieve the U. S. Post Office Department of the articles in the mail car. Things did not go exactly as planned. The dynamite they used to blow open the car scattered its contents. Worse yet, four of the train’s crew were shot by the heavily armed brothers. The attempted robbery failed for the very good reason that, as the robbers later discovered, the money they attempted to steal was never even on the train. Fleeing the scene of the crime, the brothers assumed aliases, with Hugh joining the army. He was stationed in the Philippines, where a buddy, having seen his likeness on a wanted poster, notified police of his whereabouts. After growing mustaches as a disguise, the other brothers took jobs at a steel mill, but they were followed to Steubenville, Ohio, by authorities who were not fooled by their mustaches. Charged with murdering three of the train’s crew members, Hugh pleaded not guilty, while the twins confessed. Nevertheless, all three brothers were convicted and sentenced to life in prison. Hugh died there at age 55, but the twins were paroled, Ray in 1961 and Roy in 1983, after receiving a lobotomy in 1949. Asked what had possessed him and his brothers to attempt to rob the train and kill three people in the process, Ray said, “I suppose at the time I was carrying my share of adolescent neurosis.” The attempted robbery and the murders committed by the DeAutremont brothers inspired the 1949 film Special Agent. Directed by William C. Thomas and starring William Eythe, the movie features two, rather than three, brothers, farmers Edmond and Paul Devereaux, played by Paul Valentine and George Reeves, respectively. Hoping to avert the financial disaster threatening their farm, the brothers take it upon themselves to rob a train, which puts investigating Detective Johnny Douglas hot on their trail. To lend authenticity to the production, the opening credits point out, “This picture is based on material in the official files of the American Railroads,” but cites the fictitious “Devereaux Case,” rather than the crimes of the DeAutremont brothers.[2]

8 The Hitch-Hiker

When he left prison at age 21, Billy “Cockeyed” Cook told his father that he had but one ambition in life: to live by the gun and roam. Hitchhiking in Texas in December 1950, he began living his dream as he kidnapped a driver who’d stopped to give him a ride. His victim, whom Cook had forced into the trunk of his car, escaped. The next man Cook kidnapped, 33-year-old Illinois farmer Carl Mosser, who was on his way to New Mexico, was not as fortunate, nor was his family, who was traveling with him. They made the same mistake as Cook’s first victim: they stopped to offer the hitchhiking killer a ride. After they drove to Cook’s hometown of Joplin, Missouri, Cook shot Mosser, his wife Thelma, 29; their sons Ronald, 7, and Gary, 5; and their daughter Pamela Sue, 2—and the family’s dog—before dumping their bodies down a well. Near Blythe, California, Cook kidnapped a deputy. The lawman was lucky; Cook had once worked with the deputy’s wife, who had treated him well, so Cook was generous: he spared his victim’s life. A Seattle salesman named Robert Dewey was not as fortunate. Cook shot him, dumping his corpse into a ditch. The outlaw’s murder spree ended a few days later when the killer forced two hunters to drive him to Mexico. There, Santa Rosalie Police Chief Luis Parra recognized Cook, arrested him, and turned him over to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In Oklahoma, Cook was tried and convicted of killing Mosser and his family and received a sentence of 300 years in prison. The justice system was not finished with Cook, however. In California, found guilty of having murdered Dewey, he was sentenced to death. He was executed in San Quentin’s gas chamber on December 12, 1952, at age 23, having accomplished his life’s goal “to live by the gun and roam.” As reporter Ben Cosgrove points out, in a Life magazine article concerning the killer, Cook became the subject of a movie “less than a year after he was put to death.” Written and directed by actress/director Ida Lupino and starring William Talman as Emmett Myers, The Hitch-Hiker is “one of [Hollywood’s] first films…clearly based on a killer whose crimes were still fresh in the minds of filmgoers.” [3]

7 The Night of the Hunter

Supposedly, Harry Powers was a self-described lonely heart. According to his 1939 American Friendship Society advertisement, he was a wealthy widower who earned between $400 and $2,000 a month and was worth more than $100,000. He also had a lovely “10-room brick home” in which his future wife could be more than comfortable; he promised to buy her a car and give her plenty of spending money, so she could “enjoy herself.” Chicago widow Asta Eicher, 50, thought she had found Mr. Right. A man like Powers, who called himself “Mr. Pierson” in his ad, could support both her and her children—Greta, 14; Harry, 12; and Annabel, 9—very nicely, indeed! Oddly, it seemed that the couple would live in Eicher’s house rather than his 10-room brick home. To make room for the new love of her life, who visited her frequently at home, she asked her boarder, William O’Boyle, to move out. When the former boarder returned to Eicher’s residence to retrieve some tools he had forgotten, he saw “Mr. Pierson,” but there was no sign of either his former landlady or her children. Oddly, Eicher’s boyfriend was busy carrying the family’s belongings from the house. Pierson could explain, though. Handing O’Boyle a letter, allegedly from Eicher, which supported his claims, he told O’Boyle that she and her children had moved to Colorado, asking him to take care of her outstanding personal business. Further details were unavailable, it seemed, which made O’Boyle suspicious, as it did the police, who decided an investigation was in order. Love letters led investigators to a place near Quiet Dell, West Virginia, which would acquire the nickname “murder farm.” In a garage, police found Eicher’s personal property and the bodies of Eicher, her children, and another victim, Northboro (also spelled Northborough), Massachusetts, divorcee Dorothy Lemke, age 50. Police discovered that Powers had preyed upon women for decades. A trunk on the premises contained over 100 letters to and from “loved-starved widows and spinsters from all over the country,” reports Mara Bovsun, in a New York Daily News article. His modus operandi had been to date the women, drain their bank accounts, and leave them—or, in the cases of Lemke, Eicher, and the latter’s family, kill them. Less than two hours after the jury began its deliberation, members reached a verdict. Found guilty, Powers was sentenced to hang. Before his execution on March 18, 1932, he was asked if he had any final words to offer. The man who had confessed to police that he had hanged his victims one at a time, allowing 12-year-old Harry “to watch the killing of his mother and the others,” until the boy began to scream and Powers, fearing someone hearing the boy, “picked up a hammer and let him have it,” proved strangely reticent, saying simply, “No.” [4] The Night of the Hunter (1955), directed by Charles Laughton and starring Robert Mitchum, Shelley Winters, Lillian Gish, and Billy Chapin, is loosely based on Powers’s crimes. However, the film departs significantly in some ways from its inspiration. Mitchum, as Harry Powell, a self-proclaimed minister who says he does God’s work by fleecing women out of their money before killing them, marries widow Willa Harper but encounters a problem when her children refuse to divulge the place in which their father hid the $10,000 he stole during a robbery. After killing Willa, he is arrested, and police rescue him from a lynch mob. As he is led away, however, the state’s executioner promises to see Powell again before long.

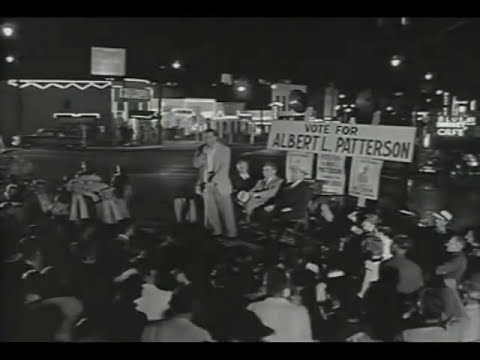

6 The Phenix City Story

Phenix City, Alabama, was a hotbed of lawlessness, both during the Great Depression when it was a refuge for bootleggers and following World War II, when nearby Fort Benning, Georgia, soldiers frequented its seedy bars, brothels, and gambling establishments. A Washington Times article points out that Albert Patterson, the Democratic candidate for state attorney general, attempted to clean the city up, but his assassination ended those efforts. It also made national headlines—and became the basis for a 1955 movie.” Patterson’s son, John, explained how corruption and vice mushroomed in Phenix City in the 1930s. The city “opted to permit illegal gambling to get the funds to run their town and pay off their bonded debt [and] folks…at the state Capitol looked the other way [and the feds] did not get involved.” Once the criminals gained control of juries and ballots, Patterson was the last hope of the good citizens of the town. Unfortunately, he was murdered on June 18, 1954. Although Circuit Solicitor Arch Ferrell was tried and acquitted, Albert Fuller, Russell County’s chief sheriff’s deputy, was convicted of murdering Patterson and spent 10 years in prison before being paroled. As a result of Patterson’s assassination, Governor Gordon Persons declared martial law and ordered the National Guard to act as local law enforcement. In addition, the local judiciary was replaced. Special agents of the state’s Investigative and Identification Division (now the Alabama Bureau of Investigation) launched an investigation, and “the organized crime syndicate running Phenix City was completely dismantled within six months.” Ultimately, it exposed the magnitude of the corruption and criminality that Patterson had opposed in Phenix City. Once the investigation was complete, the grand jury brought 734 indictments, including charges against many law enforcement officers, local business owners connected to organized crime, and elected officials. The Phenix City Story (1955) is based on Patterson’s assassination. Directed by Phil Karlson, the movie makes Rhett Tanner (Edward Andrews) the city’s crime lord, who runs the town’s bars, brothels, and gambling establishments, while paying off the police. When political candidate Albert “Pat” Patterson (John McIntire) promises to clean up the corruption and vice, he is murdered, and his son John (Richard Kiley), having returned home after serving in the military, vows to avenge his father’s death.[5]

5 While the City Sleeps

William Heirens, 17, the notorious “Lipstick Killer,” spent 65 years and 181 days of his three consecutive life sentences in prison, the last at the Dixon Correctional Center in Dixon, Illinois. That is where he died in 2012, at the age of 83, his confession to three murders having landed him in prison on November 15, 1928. The novel The Bloody Spur, by Charles Einstein, is based on Heirens’s heinous crimes. The book became the basis of the 1956 movie While the City Sleeps. The killer’s victims included two women, Josephine Ross and Frances Brown, and 6- or 7-year-old Suzanne Degnan (accounts differ regarding her age). Brown had been stabbed through the neck and shot in the head. Ross had been stabbed repeatedly in the neck. Regarding all three victims, the killer’s motive, he confessed to police, was the same: sexual pleasure. A contemporary account of the police’s investigation of the kidnapped child’s murder, which appeared in The Daily Banner, a Greencastle, Indiana, newspaper, describes the results of the horrific crime: “The child’s blonde, curly head, her legs and torso were found…in separate cesspools within a one-block radius of her parents’ home.” An ax had been used to dismember and decapitate her, police said. While the City Sleeps (1956), directed by Fritz Lang, departs quite a bit from the actual crimes, focusing on a contest among a news company’s journalists to identify the serial murderer known as the “Lipstick Killer” (John Drew Barrymore). The winner received a promotion, becoming the organization’s new executive producer. The film also stars Dana Andrews, Rhonda Fleming, Ida Lupino, and George Sanders.[6]

4 Butterfield 8

Starr Faithfull was a beautiful young flapper who, according to her diary, lived what police characterized as a promiscuous lifestyle that involved sexual escapades with 19 men. Her parents were poor, but her wealthy cousins paid her tuition at Rogers Hall Academy in Lowell, Massachusetts, an exclusive boarding school. Unfortunately, an adult cousin, Andrew J. Peters, “doused her with ether…and seduced her,” often taking her on overnight road trips with him. As a teen, she behaved oddly at times, hiding her femininity by wearing boy’s attire. After her parents divorced and her mother, Helen, married Stanley Faithfull, Starr took his name as her surname. She began attending parties, abused alcohol, barbiturates, and inhalers. She behaved erratically and, on one occasion, overdosed on “sleeping drugs.” When she reported Peters’s abuse to her mother, Peters bought Helen’s and Stanley’s silence. On June 8, 1931, Faithfull’s body was found on a deserted beach amid some seaweed. Perhaps intending to stow away aboard a ship bound for the Bahamas, she had drowned, her autopsy revealed, but “bruises suggested she had had help.” Neither an investigation nor an inquest determined whether Faithfull’s death had resulted from murder or suicide. Still, her diary mentioned “AJP” as one of the men with whom she had had a sexual liaison. The public wondered whether the initials stood for her cousin, Andrew J. Peters, especially after Faithfull’s stepfather, believing her to have been murdered, confronted the district attorney about the case, accusing him of poorly investigating and prosecuting the case. He even gave the D.A. the agreement Peters had him sign in 1927 with a copy of the check he received—for $20,000—to “hold Peters harmless.” After Faithfull’s death, it was reported that peters had a nervous breakdown. On the other hand, Dr. George Jameson Carr revealed that Faithfull had sent him letters, one of which referred to her dull and worthless life, declaring her desire for “oblivion.” Whether murder or suicide claimed Faithfull’s life, it seems clear that her cousin’s sexual abuse may well have contributed to her demise. The story of Faithfull’s fateful life is the basis of Butterfield 8 (1960), directed by Daniel Mann, in which Elizabeth Taylor reluctantly plays Starr Faithfull. A later biography revealed that she did not want to play the part but was under contract with MGM Studios, who forced her to star in the film. Despite her reluctance to portray Faithfull, Taylor won an Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance in Butterfield 8.[7]

3 Mad Dog Coll

Critics were not kind to Mad Dog Coll (1961). The New York Times’s reviewer Harold Thompson thought the film “belongs back in the pound.” Directed by Burt Balaban, the movie stars John Davis Chandler as Mad Dog Coll and Vincent Gardenia as Dutch Schultz; Telly Savalas appears as Lt. Darro. The film opens with a memorable scene: Coll machine-gunning his abusive father’s headstone. As the leader of a street gang, he keeps his Tommy gun handy and never hesitates to use it to spray his enemies with bullets. In general, the movie’s plot plays fast and loose with the life and crimes of Vincent “Mad Dog” Coll. The sensationalized nature of the film is made clear to prospective audiences by its poster’s description of the hitman as a “maniac with a machine gun” and his terrifying effect on crime lords who “tremble when Killer Coll calls.” That’s not to say that Coll was anything but a vicious, ruthless killer, the worst of his acts being the killing of a child, albeit accidentally. Active during Prohibition, Coll was wild and unpredictable, and he was reckless. After Dutch Schultz killed his brother Peter in May 1931, Coll sought revenge by hunting down and killing four of Schultz’s men in the next three weeks. In addition, his gang and Schultz’s continued to face off—often amid gunfire—in the streets of New York, where many men fell dead. In June, as he attempted to kidnap rival bootlegger Joseph Rao, a spray of his bullets struck five children, killing a five-year-old boy. The horrendous deed resulted in New York’s Mayor Jimmy Walker calling Coll a “Mad Dog.” Later brought to trial, Coll was acquitted, only to be shot on February 8, 1932. At age 23, Mad Dog was dead.[8]

2 10 to Midnight

10 to Midnight, the 1983 movie directed by J. Lee Thompson and starring Charles Bronson as Detective Leo Kessler, is based on the murders committed by Richard Speck. The criminal’s cinematic counterpart, Warren Stacey (Gene Davis), is an amoral, nearly psychotic serial killer who delights in the murder of naked women—with himself also in the nude. Willing to do whatever needs to be done to take the ruthless killer off the street, Kessler plants evidence, despite his partner’s objections, and, when the suspect is released on a technicality, goes after him: a cop turned vigilante. The particulars of Richard Speck’s crimes are fairly well known. On July 14, 1966, he killed eight women, all student nurses, in a Chicago townhouse. The horror of the killings came back to John Schmale when he discovered a cardboard box in his basement after inspecting the cellar after it had flooded. The box contained four carousels of slides, heavily damaged and water-logged. They were part of the legacy left to him by his father. The slides included images of his sister Nina, one of Speck’s victims. Ironically, Speck’s deeds made him infamous, while his victims have been largely forgotten. Schmale believed they should be remembered: Nina Jo Schmale, Patricia Ann Matusek, Pamela Lee Wilkening, Mary Ann Jordan, Suzanne Bridget Farris, Valentina Pasion, Merlita Gargullo, and Gloria Jean Davy. The 2007 horror movie Chicago Massacre is also based on the Richard Speck murders. It was directed by Michael Feifer and stars Corin Nemec as Speck. The film begins with the father’s abuse of the main character as a child, which causes the boy to run away from home. Subsequently, he marries, is divorced, and begins his torture-and-murder spree. Afterward, he drifts until an attempt at suicide lands him in a hospital, where a doctor spots a tattoo that alerts him to the fact that his patient is wanted by the authorities. Speck is arrested, tried, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison, where he dies.[9]

1 To Die For

Although accounts of high school educators, both male and female, having sex with students have increased dramatically in recent years, such trysts were far less common—or perhaps only far less commonly reported—in the past. In 1990, one such case involved 22-year-old Pamela Smart, a New Hampshire high school media coordinator found guilty of conspiring with a student, William Flynn, then 15, with whom she was having an affair, to kill her husband. To this day, Smart, now 54, says she never asked Flynn to kill anyone, but she has been twice denied a reduction of her life sentence. The murder of Smart’s husband, Greggory, inspired the 1995 movie To Die For, directed by Gus Van Sant. It stars Nicole Kidman as Suzanne Stone-Maretto, a Smart-like woman seeking independence from her husband Larry Maretto (Matt Dillon), and Joaquin Phoenix as Jimmy Emmett, the teen she seduces into murdering Larry. As might be expected, details of the film’s plot differ somewhat from those of the true crime on which the movie is based. Stone-Maretto, an aspiring television journalist, wants her husband dead for reasons that differ from Smart’s motive. Likewise, in the actual crime, the Mafia played no role in avenging the husband’s death, as the mob does in the film. Art may imitate life, but the two are seldom the same. Although the movie was generally well-received, one person did not care for Kidman’s portrayal of the murderous seducer—Smart herself. Smart found the Academy Award-winning actress’s representation of her both embarrassing and inaccurate as well as simplistic. Although Smart considers Kidman an acclaimed actress, the convicted killer finds Kidman to have played her as though Smart is a complete airhead and points out that Kidman never consulted her about how to play the part. Instead, the actress “played a one dimensional character.” Smart insisted, “I’m not that person.” [10]