10Marriage Was A Mere Agreement

Girls married during their early teens while men tied the knot in their mid-twenties. Roman marriages were quick and easy and most didn’t flower from romance but from two agreements. The first would be between the couple’s families, who eyeballed each other to see if the proposed spouse’s wealth and social status were acceptable. If satisfied, a formal betrothal took place where a written agreement was signed and the couple kissed. Unlike modern times, the wedding day didn’t cement a lawful institution (marriage had no legal power) but showed the couple’s intent to live together. A Roman citizen couldn’t marry his favorite prostitute, cousin, or, for the most part, non-Romans. A divorce was granted when the couple declared their intention to separate before seven witnesses. If a divorce carried the accusation that the wife had been unfaithful, she could never marry again. A guilty husband received no such penalty.

9Feast Or Famine

Social position determined how a family ate. Lower classes mostly had simple fare while the wealthy often used elaborate feasts to showcase their status. Bread featured heavily at both breakfast and lunch. While the lower classes added olives, cheese, and wine, the upper class enjoyed a better variety of meat, feast leftovers, and fresh produce. The very poor sometimes just ate porridge or handouts. Meals were prepared by the women or slaves of the household, and the children served them. Nobody had forks, so food was consumed using their hands, spoons, and knives. Dinner parties of the Roman rich were legendary for their decadence and delicacies. Lasting hours, guests reclined on dining couches while slaves cleaned up the discarded scraps around them. All classes relished a stomach-churning sauce called garum. Basically the fermented guts of fish, it reeked so bad that it was forbidden to make it within city limits.

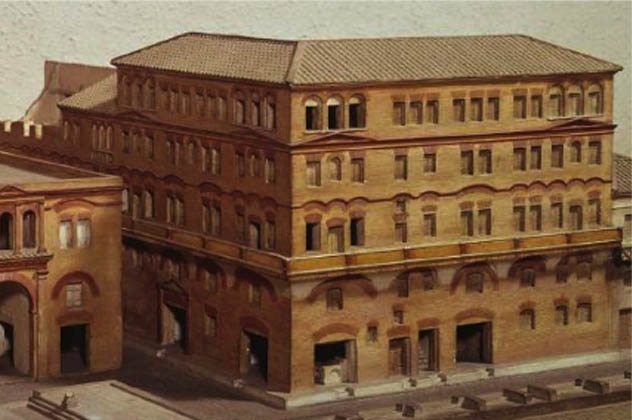

8The Insulae And Domus

One’s neighborhood pretty much depended on how high up the totem pole you were. Insulae were apartment buildings, but the kind that would make a modern safety inspector hit the roof. The majority of the Roman population lived in these seven-story-plus buildings. They were ripe for fire, collapse, and even flooding. The upper floors were reserved for the poor who had to pay rent daily or weekly. Eviction was a constant fear for the families living in a one-room affair with no natural light or bathroom facilities. The first two floors of an insulae were reserved for those who had a better income. They paid rent annually and lived in multiple rooms with windows. Wealthy Romans either lived in country villas or owned a domus in the city. A domus was a large, comfortable home. They were big enough to include the owner’s business shop, libraries, rooms, a kitchen, pool, and garden.

7Marital Sex

Things in the Roman bedroom weren’t exactly even. While women were expected to produce sons, uphold chastity, and remain loyal to their husbands, married men were allowed to wander. He even had a rule book. It was fine to have extramarital sex with partners of both genders, but it had to be with slaves, prostitutes, or a concubine/mistress. Wives could do nothing about it since it was socially acceptable and even expected from a man. While undoubtedly there were married couples who used passion as an expression of affection for one another, the general unsympathetic view was that women tied the knot to have children and not to enjoy a great sex life. That was for the husband to savor, and some savored it a little too much—slaves had no rights over their own bodies, so the rape of a slave was not legally recognized.

6Legal Infanticide

Fathers held the power of life or death for a newborn, even without the mother’s input. After birth, the baby was placed at his feet. If the father picked it up, the child remained at home. Otherwise, it was abandoned outside for anyone to pick up—or to die of exposure. Roman infants faced rejection if they were born deformed, a daughter, or if a poor family couldn’t support another child. If the father was suspicious about the kid’s real paternity, he or she could be dumped near a refuge area. The lucky ones were adopted by childless couples and received the family’s name. The rest risked being sold as slaves or prostitutes or being deliberately maimed by beggars who displayed such children to get more sympathy. If older children displeased their father, he also had the legal backing to sell them as slaves or kill them.

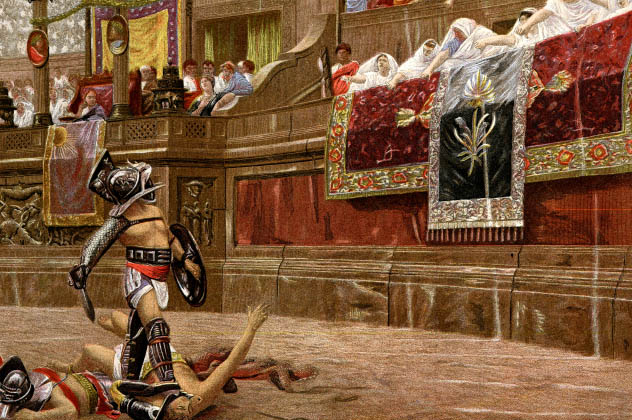

5Leisure For The Family

Downtime was a big part of Roman family life. Usually, starting at noon, the upper crust of society dedicated their day to leisure. Most enjoyable activities were public and shared by rich and poor alike, male and female—watching gladiators disembowel each other, cheering chariot races, or attending the theatre. Citizens also spent a lot of time at public baths, which wasn’t your average tub and towel affair. A Roman bath typically had a gym, pool, and a health center. Certain locales even offered prostitutes. Children had their own favorite pastimes. Boys preferred to be more active, wrestling, flying kites, or playing war games. Girls occupied themselves with things like dolls and board games. Families also enjoyed just relaxing with each other and their pets.

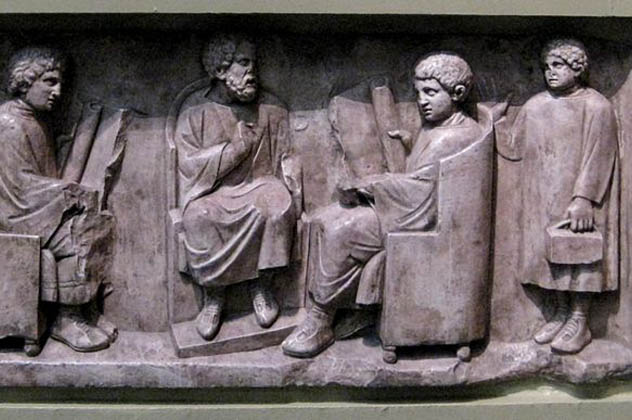

4Education

Education depended on a child’s social status and gender. Formal education was the privilege of high-born boys, while girls from good families were only allowed to learn how to read and write. Schooling in Latin, reading, writing, and arithmetic were usually the mother’s duty until age seven, when boys received a teacher. Affluent families had private tutors or educated slaves for this role; otherwise, the boys were sent to private schools. Education for male pupils included physical training to prepare them for military service as well as later assuming a masculine role in society. Country folk or children born of slaves received little to no formal education. To them it was more practical that sons learn their trades from their fathers and little girls learn housekeeping. There were no public schools for disadvantaged children to attend. The closest thing was informal get-togethers that were run and taught by freed slaves.

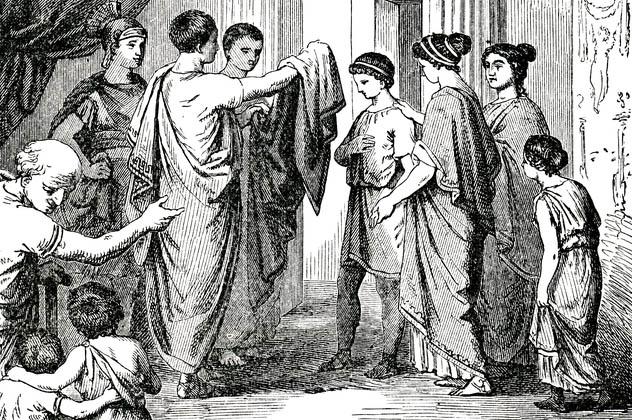

3Coming Of Age

While daughters crossed the threshold of adulthood almost unnoticed, a special ceremony marked a boy’s transition to manhood. Depending on his mental and physical prowess, a father decided when his son was grown (usually around 14–17). On the chosen morning, the youth discarded his bulla and childhood toga, and a sacrifice was given. His father then dressed him in the white tunic of a man. If the older man had rank, the tunic reflected this—two wide crimson stripes if he was a senator and slim ones for a knight. The last of the new clothing was the toga virilis or toga libera, worn only by adult males. The father then gathered a large crowd to escort his son to the Forum. Once there, the boy’s name was registered, and he officially became a Roman citizen. After that, the new teenage man could expect an apprenticeship for a year in a profession of his father’s choosing.

2Pets

When it comes to ancient Rome’s animal policies, one can be forgiven if the first image that comes to mind is gory slaughter at the Colosseum. However, private citizens cherished their household pets. Dogs were by far the favorite, but cats were not uncommon. House-snakes were appreciated as ratters, and domesticated birds were also delighted in. Nightingales and green Indian parrots were all the rage because they could mimic human words. Cranes, herons, swans, quail, geese, and ducks were also kept. While the last three proved very popular, Roman fondness and treatment of peacocks was almost on par with dogs. Some cruelty existed in bird fighting, but it wasn’t a widespread sport. Roman pets were so deeply loved that they were immortalized in art and poetry and even buried with their masters. Other pets included hares (a popular gift exchanged by lovers), goats, deer, apes, and fish.

1Women’s Independence

Ancient Rome wasn’t an easy place to be a woman. Any hopes of being able to vote or of following a career was about as possible as a modern person trying to pluck a diamond out of thin air. Girls were sidelined to a life in the home and childbirth, suffering a philandering husband (if he was so inclined), and having little power in the marriage and no legal claim to her children. However, because child mortality was so high, the state rewarded Roman wives for giving birth. The prize was perhaps what most women dearly wanted: legal independence. If a free-born woman managed three live births (four for a former slave), she was awarded with independent status as a person. Only by surviving this serial-birthing could a woman hope to escape being a man’s property and finally take control over her own affairs and life. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages