10 Cappadocia’s Vast Underground City

With over 200 underground cities and villages as well as hand-carved caves which sheltered some of the earliest Christians, Turkey’s Cappadocia region is historically one-of-a-kind. Long ago, researchers unearthed a large subterranean settlement known as Derinkuyu. Recently, they dug up another multilevel settlement that served as the world’s biggest safe room. Its total size is unknown, but to call it sprawling is an understatement. Archaeologists estimate its area at approximately 5 million square feet, and it goes as deep as 113 meters (371 ft). Further exploration is a priority, but it’s slow going, as the surrounding rock is fluffy and prone to collapse. This crumbly, marshmallow-soft volcanic landscape is what allowed the Cappadocians to carve such an intricate network of tunnels so deep into the ground. The complex was fully furnished, in a manner of speaking, with a healthy water supply and ventilation system. Impressively, some of the 5,000-year-old tunnels are wide enough to accommodate a family sedan. Furthermore, the settlement housed siege-resistant luxuries like wineries, chapels, and even a “refinery” for producing lamp oil.

9 The Legendary City Of Gath

Archaeologists have located the legendary city of Gath after a 20-year excavation effort led by Israel’s Bar-Ilan University. One of the five Philistine city-states, Gath is the reported home of the Biblical giant Goliath, who “relinquished” his seat to David, future king of Israel and first in a procession of great rulers. Separate expeditions have been carried out since 1899, turning up some smaller items, but researchers have only recently been able to confirm the Biblical city’s existence. Researchers unearthed a mammoth gate, the largest ever discovered in Israel, which they believe to be the very same gate referenced in the Book of Samuel. It’s a fitting entrance for one of the region’s major cities in the 9th or 10th century BC. Israelite-style Philistine pottery was also recovered, suggesting at least a partial meshing of cultures between the two enemies. Gath was an Iron Age city of industry. Archaeologists also discovered a prominent foundry within its confines, painting Gath as a bustling urban center that supplied nearby communities with varied metalwork.

8 Wealthy Urbanite Fresco

The Museum of London Archaeology has discovered a wonderfully preserved, nearly 2,000-year-old fresco owned by ultra-wealthy urbanites. On this same site once stood London’s Roman basilica and forum, a two-hectare complex erected in 70 AD. Larger than St. Paul’s Cathedral, the island nation’s grandest building served both as a civic center and London’s party central. At least, it did for a few centuries; the Romans tore it down in 300 AD to punish Londoners for their support of Emperor Carausius. Commissioned by an affluent family, the fancy fresco was painted by a supremely skilled artisan and depicts natural scenes, replete with nibbling deer and flitting birds. Its patrons spared no expense, importing rare, expensive pigments like cinnabar, a ridiculously toxic mercuric sulfide mined in Spain. In the days before sports cars, the rich flaunted paintings to advertise their importance. As in modern times, families jostled to one-up each other with grander artworks crafted from luxurious materials that were inaccessible to the poor. The fresco also records an ancient OSHA violation. Researchers found it face-down, suggesting that subsequent builders simply stacked new materials on top of rubble after the original structure had been razed.

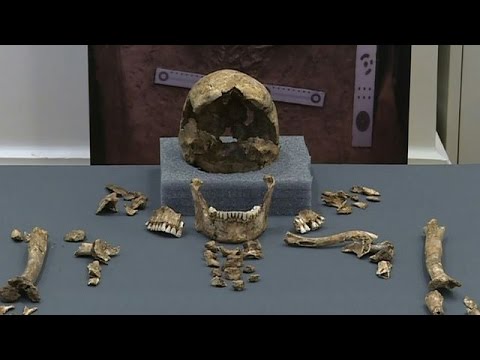

7 Jamestown’s First Settlers

Researchers have uncovered four skeletons that belonged to some of the first settlers at Jamestown, Virginia, the first permanent colonial outpost in what would become the United States. The men, aged 24–39, died between 1608 and 1610 and were buried in the chancel of the very same church that wed of Pocahontas and John Smith. The skeletons were in poor condition, and only about a third of each one remained. Ascertaining the men’s identities required a few years of high-tech sleuthing. The church burial offered the first clue, since only prominent figures or clergymen could be interred in such a plot. Eventually, after chemical analyses, genealogical mapping, CT scanning, and even a touch of 3-D printing, the dead finally relinquished their secrets. They were elite members of society—Captain William West and Reverend Robert Hunt (who arrived with the first wave of settlers in 1607) and their grave mates, Captain Gabriel Archer and Sir Ferdinando Wainman (both of whom arrived a few years later). Several other curios hinted at their status. Traces of lead, from pewter dining utensils, were found in their bones. There was also a captain’s sash made of silk and embroidered with silver finery. Oddly enough, archaeologists also found a small silver box—a Catholic reliquary, an unexpected burial relic in a Protestant settlement and the New World’s first Protestant church.

6 Tenochtitlan Sacrifices

The Aztec (aka Mexica) rulers were a bloodthirsty bunch. They sacrificed thousands of captured warriors upon the pedestal at the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan to feed the heart-hungry god of war, Huitzilopochtli. So say historical sources, though a study conducted by archaeologist Alan Barrera tells a different story. Apparently, the Aztecs were far less discriminating than previously assumed, and sacrifices were not limited to soldiers and able men. Women, the elderly, and even children were forced to take their places atop the Great Temple. Barrera and colleagues sampled pieces of bone and teeth extracted from sacrificial victims to ascertain the abundance of strontium isotopes to reveal where the sacrificed ones had lived. Surprisingly, these unlucky individuals were locals and residents, not foreign prisoners as previously assumed. Some poor souls had even lived among the Aztecs for years, possibly as slaves to those of high status, before they were rewarded for their toil with an obsidian dagger to the chest.

5 Genghis Khan’s Wall

Apparently, the Great Wall of China may be a slight misnomer. In 2012, British researcher William Lindesay stumbled upon a still standing, long forgotten remnant . . . in Mongolia. Lindesay literally walked alongside the Great Wall, tracing its path on an epic, 2,460-kilometer (1,530 mi) walking journey that began in 1986. Well over a decade later, Lindesay’s persistence was rewarded with the rediscovery of what’s been called “Genghis Khan’s Wall,” though it wasn’t built by the fearsome ruler and appears to be a lost portion of the Chinese Great Wall. Previously, researchers had only glimpsed its skeletal remains, a faint 100-kilometer (60 mi) outline stretching across the Gobi, but the portion found by Lindesay stands shoulder height and was at least 2 meters (6 ft) higher in its heyday. It was completed between AD 1040 and 1160, after about 100 years of effort. However, its purpose is unknown. The absence of tools, weapons, and outposts suggest that it was never manned, possibly because its builders scrapped the project to build elsewhere. Ancient texts claim that Ogedei Khan, son of Genghis, commissioned this “ghost wall” to rein in gazelle. But researchers disagree, claiming this area of desert to be notoriously sparse.

4 Maya Animal Survey

Knowledge of Mayan culture is disproportionately top-heavy, and our purview is mostly limited to the upper classes. Fortunately, a recent survey of 22,000 animal remains from three Guatemalan city-states, including the well-fortified ancient capital of Aguateca, has finally revealed the lives of the Maya’s 99 percent. Researchers found a surprisingly intricate trading network between the city-states, based on availability of animal food sources. Unlike their contemporaries in the Old World, Central Americans did not have the convenience of pack animals and were unable to carry large quantities of goods. What they did pilfer from the sea and woods they hauled on their backs through unforgiving jungle terrain, so trade became especially important and each region gained fame for its signature export. For example, Aguatecan city-slickers enjoyed an abundance of marine species and produced exquisite seashell jewelry, while their compatriots in Yaxchilan were limited to forest-dwelling ungulates like deer. In culinary terms, the social classes did not intermingle. Each class had access to different types of animals, which provided not only food but social status. Jaguars and crocodiles considered the most sacred of creatures and only associated with the upper echelon. The remains also suggest that the Maya regulated hunting and fishing, showing great respect for natural supply and demand.

3 Stonehenge Builders’ Diet

Researchers have unearthed a variety of crusty pots and animal bones at a large settlement adjacent to Stonehenge called Durrington Walls, glimpsing the ancient diets of Neolithic workmen. It turns out that they really loved milk. The 4,500-year-old residues scraped from containers show an abundance of dairy products, possibly in the form of cottage cheese. The affinity for curdled goods was downright mystical, with traces of the stuff found on ceremonial monuments. The builders enjoyed plenty of meat as well, and old cookware shows that they dined on the boiled meats that have become so famous in England. The site apparently had a supply of livestock, and animals were slaughtered on-site, powering the builders’ workload with mass amounts of pork and beef. The patterns on the bones themselves show that the builders liked to shake things up and sometimes orchestrated large communal cookouts. The only thing missing—vegetables. There were no signs that any greens were prepared at the site, with non-animal food sources limited to a trail mix of hazelnuts, crab apples, and wild berries.

2 ‘New’ Nazca Lines

Several hundred miles south of Lima, the fantastic Nazca Lines are etched across nearly 500 square kilometers (200 mi2) of Peru’s coastal plain. Now, researchers from Japan’s University of Yamagata have found an even older set of glyphs that predate the famed UNESCO animals by hundreds of years. The team used 3-D scanning to reveal the dusted-over outlines of 41 images, emblazoned by the avid headhunters who inhabited the region between the first century BC and the fifth century AD. This batch was more carefully made, as the pebbles within the body of each image have been removed, revealing the white, chalky ground beneath. The more well-known Nazca Lines, on the other hand, are merely outlined. The figures, some of which represent the llama, a South American spirit animal, are usually inscribed on hillsides for proper visibility and reach heights of 20 meters (66 ft). Researchers believe that at least some of these lines traced the routes of long-ago pilgrimages. The Yamagata group also unearthed the remnants of nearby temples, and it appears that the lines led ancient processions between Peru’s ancient holy sites, like a modern Hollywood star map. Unfortunately, one ancient ritual consisted of smashing clay pots upon the lines, destroying parts of the original artwork.

1 Shakespeare’s Fancy Digs

Stafford University’s Centre of Archaeology, in collaboration with the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, has dug up the Bard’s kitchen. This most recent discovery has allowed for a reconstruction of the home, known as New Place, in which Shakespeare spent his most fruitful years. Based on his sprawling home, Shakespeare was doing quite well for himself. It was the largest residence in the Borough of Statford-upon-Avon, with 20 rooms, a gallery, a cavernous chamber, and 10 fireplaces. The unearthed kitchen was equipped with a hearth, an interior fridge (basically a cold pit), and most impressively of all, an in-home brewery. So, how much did such a magnificent structure cost in 1597? £120! The dig was part of a £5.25 million restoration project with the ultimate goal of displaying the historic home in honor of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, like an ancient version of Cribs. New Place will open to the public circa July 2016 and will also feature recreations of plates, utensils, and other items unearthed at New Place.