10 The Poison Squad

Food, drinks, supplements, and pharmaceutical drugs available in the United States are all heavily regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in order to ensure public health. This is mostly thanks to the efforts of a chemist named Harvey Washington Wiley (pictured above). He lobbied for the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which led to the creation of the FDA. Wiley even served as the board’s first commissioner. Before that, Wiley worked for the US Department of Agriculture. This included a colorful five-year stint where Wiley’s job was to test the safety of every food additive on the market. He used 12 volunteers who were willing to follow a strict regimen and waive their rights to sue the government for any injuries sustained during the process. And since Wiley was a complete misogynist who thought anything remotely scientific would be too complicated for a woman to understand, all his volunteers were young men. Rather dully, Wiley named his project the “hygienic table trials,” but the Washington Post found a better moniker for his crew—the Poison Squad. Each day, the 12 volunteers would eat three meals laced with the chemical du jour. They had checkups before every meal, and they underwent physical examinations once a week. Plus, they were required to regularly hand over urine, hair, sweat, and stool samples. During these trials, the Poison Squad “enjoyed” additives such as borax, formaldehyde, and sulfuric acid. Unsurprisingly, they got sick along the way. However, the results caused a public outrage and made clear that the US needed a governing body to regulate food products.

9 The Ejection Tie Club

In 1934, engineer James Martin and Captain Valentine Baker founded the Martin-Baker Aircraft Company, a business specializing in aviation safety equipment. After World War II, they saw a need for all standard aircraft to be fitted with an ejection system. Since their first live test in 1946, Martin-Baker ejection seats have saved well over 7,000 lives. To celebrate their accomplishments, the company also started the exclusive Ejection Tie Club. Lifetime membership is awarded to anyone who ejects from an aircraft in an emergency situation using a Martin-Baker ejection seat. Plus, they have to live to tell the tale, naturally. The first “inductee” into this club was an RAF pilot who ejected over Rhodesia in 1957. Since then, club membership has increased to over 5,800. But details regarding the members are murky. After all, many of these members are still in active service. In addition to bragging rights, members receive a certificate, a membership card, a patch, and a pin (or a brooch for female pilots). Most important, however, is the signature tie that allows club members to show off when they aren’t in uniform. Despite the efficiency of ejection seats, pilots are in no rush to join the club. Ejecting from a plane is a bumpy ride, even in ideal conditions. For starters, ejection feels like a powerful punch to the chest that leaves you breathless and stiff. If you look down while falling, you’re likely to injure your neck, and you’ll be lucky if you walk away from the landing without leg or spinal injuries.

8 The Shuttlecock Club

Skeleton is a winter sport that involves sledding down a frozen track at speeds exceeding 130 kilometers (80 mi) per hour. Unlike similar sports, such as bobsleigh or luge, skeleton involves a single athlete lying facedown on a small, thin sled. The athlete then uses her head and shoulders to steer the sled. This sport is actually derived from a form of sledding popularized on the infamous Cresta Run in St. Moritz, a town located in the Swiss Alps. Sledding became popular in Europe during the late 19th century, and the Cresta Run was built in 1884, under the supervision of the St. Moritz Tobogganing Club (SMTC). They were among the first to realize that sledding headfirst, although incredibly dangerous, actually improved speed and steering. Cresta sledding, as it would come to be known, differs from standard sledding in that riders use rakes attached to their feet to steer. Today, the Cresta Run remains one of the few tracks in the world dedicated solely to skeleton. Shockingly, it’s also closed to women. The Cresta Run features a dangerous corner called the Shuttlecock. It is a long, raking, left-hand bank about halfway through the track. It acts as a safety valve to slow riders down, but anyone who doesn’t take the corner properly risks falling out of the track. If they manage to escape their ordeal unscathed, they become automatic members of the Shuttlecock Club. They are awarded a special tie that signals their membership, and they’re entitled to attend a members-only annual dinner. The fall:ride ratio for the Shuttlecock is approximately 1:12, although it’s significantly higher for beginners.

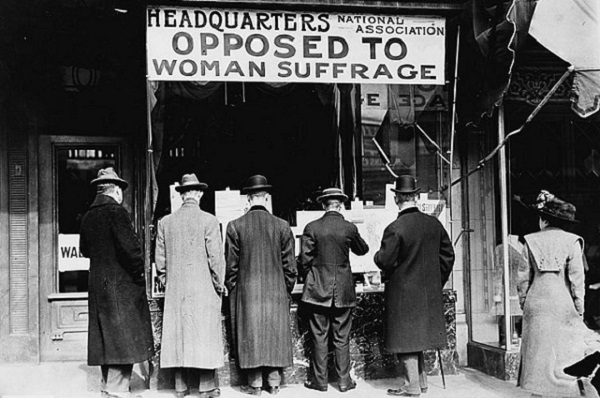

7 The National Association Opposed To Woman Suffrage

The National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS) was an organization that fought against the suffrage movement. At first glance, this doesn’t seem particularly bizarre. There were many organizations that didn’t want women gaining the right to vote, but the NAOWS had one unique characteristic. It was founded by a woman. Josephine Dodge, daughter of a former US postmaster general and member of an elite New York family, had been fighting the suffrage movement for decades before starting the NAOWS in 1911. She had no problem finding plenty of female activists who shared her conviction that women should stay out of politics. These anti-suffragettes typically belonged to wealthy families who feared suffrage would upset the status quo. In the South, the NAOWS gained support from many plantation owners who believed rights for women would lead to rights for minorities. Of course, these reasons didn’t really apply to the working class, so the NAOWS pushed other agendas to appeal to the masses. They branded suffrage as a threat to femininity. Politics was a dirty business, and if a female were to involve herself in this “manly” world, she would lose the privileges of womanhood. More importantly, suffrage threatened a woman’s ultimate vocation: motherhood. There were other women’s groups that shared the beliefs of the NAOWS. In the UK, one of the main opponents of suffrage was the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League. This group lasted for 10 years and had over 100 branches at the height of its popularity.

6 Home, Washington

In 1895, three anarchists set off along the Puget Sound to find the perfect spot for their new, idyllic community. They found it on the Kitsap Peninsula, and they named their new utopia Home, Washington. The trio soon formed the Mutual Home Colony Association, which was the only governing body in the commune. Its goals were to promote the anarchist philosophy. In a few short years, Home almost resembled a proper town, and it even attracted notable figures like writer Elbert Hubbard and anarchist Emma Goldman. They were joined by many other social outcasts who relished the freedoms they were afforded in Home. At first, the commune was ignored by outsiders. However, things changed after President William McKinley’s assassination at the hands of anarchist Leon Czolgosz. Afterward, people became more suspicious of the town. Nearby newspapers, particularly in Tacoma, painted a vivid picture for their readers of the sex-filled debaucheries that allegedly took place in Home. On several occasions, the residents were even victims of vigilante groups. That’s not what brought the end of Home, though. The group dismantled due to internal strife over one particular issue . . . skinny-dipping. The practice was started by the Russian members of the town, a clique known as the Dukhobors. They would often leave home naked and stroll to the beach for a swim. Some joined in, but others were uncomfortable with the nudity. Eventually, the town split into two groups: the “nudes” and the “prudes.” In the end, the issue proved too difficult to overcome, and the Association was dissolved in 1919.

5 The Pollywogs

A pollywog is a sailor who hasn’t crossed the equator yet. It’s a term that originated hundreds of years ago, when such an undertaking posed a serious threat. Once a seaman made his first crossing, he was upgraded from a pollywog to a shellback. However, before graduation, he would have to pass the ceremony of Crossing the Line. This tradition has been around for centuries and was observed by many sea-faring civilizations. Therefore, the details involved have changed over the years. At its worst, it was a brutal hazing ritual where pollywogs were beaten, whipped, and even thrown overboard and dragged through the surf. Fortunately, for most of its existence, the line-crossing ceremony has been a celebratory occasion, one meant to boost morale and show the new shellback’s seaworthiness. After crossing the equator, pollywogs receive an order to appear before King Neptune. Senior shellbacks dress up as Neptune and his royal court, and the pollywogs have to entertain them with an impromptu talent show. Afterward, the pollywogs must endure various “punishments.” These might include crawling through something gross or wearing questionable clothing like a mermaid outfit. One crucial ritual is “kissing the royal belly.” A senior officer dresses up as the royal baby—and sometimes slathers himself in grease—so pollywogs can kiss his belly. If they pass, they’re declared Sons (or Daughters) of Neptune. Even Charles Darwin was initiated aboard the Beagle. According to his diary, he was shaved using pitch and paint as lather, and afterward, he was dunked into the water.

4 The Flat Hat Club

Established in 1750 at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, the Flat Hat Club had the distinction of being one of the earliest collegiate societies in the United States. The official name of the group was the FHC Society, an acronym that stood for “fraternitas, humanitas, et cognito.” However, it became better known as the Flat Hat Club, based on the mortarboard caps worn at the college at the time. (These hats are now worn by students at graduation ceremonies.) The club was only around for a few decades. It officially suspended all activities in 1781 when Williamsburg was thrust into the American Revolution. However, the club had other problems due to a lack of structure or any meaningful goals. The club’s most famous member, Thomas Jefferson, later recalled that the society had no useful purpose. He was unaware whether it even still existed as there was little incentive for members to stay in touch after graduation. The club sealed its own fate in 1776 by creating its biggest competitor. It denied admission to law student John Heath, and spurred by the club’s rejection, he founded Phi Beta Kappa, the first Greek-letter fraternity in the US. A few years later, the Flat Hat Club was no more, while Phi Beta Kappa remains the oldest honor society in America still active today.

3 The Jumping Frenchmen Of Maine

The Jumping Frenchmen of Maine were a 19th-century group of lumberjacks (and their relatives) who exhibited an extreme startle reflex. They would jump or perform uncontrollable, exaggerated movements when prompted by sudden noises or unexpected physical contact. The Jumping Frenchmen were first studied by American neurologist George M. Beard. The people afflicted by this bizarre illness seemed to be concentrated in the Moosehead Lake region of northern Maine, with a few others in Quebec. Beard observed them for almost two years and presented his findings at the Sixth Annual Meeting of the American Neurological Association in 1880. His paper, titled “Experiments with the Jumpers or Jumping Frenchmen of Maine,” examined 50 separate cases, 14 of which were found in four families. Beard concluded that the extreme startle response was familial, began in childhood, and was rarely seen in women. In some extreme cases, people would instantly follow a sudden command, even if it meant hitting a loved one. Afterward, they sometimes exhibited echolalia or echopraxia, meaning they would imitate the words or movements of others, respectively. Since there were very few documented cases of this affliction, medical professionals found it hard placing the illness. While Beard thought it was an extreme form of startle reflex, others argued it could be a culture-bound syndrome. After all, it was localized to a small region. George Gilles de la Tourette considered it a typology of “convulsive tic illness,” something we now know as Tourette’s syndrome.

2 The Mad Travelers

Dromomania is a psychological urge characterized by an uncontrollable desire to travel. It is sometimes equated to wanderlust, but there is a key difference. Dromomania (also known as “traveling fugue”) implies a compulsion where the patient may or may not travel against his own wishes. In fact, he might not even remember what happened afterward. Dromomania became the hot, new thing in late 19th-century France. This was the result of a famous case published by a student named Philippe Tissie in 1887. His paper was called “Les Alienes Voyageurs” (“The Mad Travelers”). Tissie presented the case of Jean-Albert Dadas. He was a gas fitter from Bordeaux who deserted the army in 1881. He then began traveling the world, although he later claimed to remember little of his adventures. After piecing together his itinerary, it was revealed that Dadas went to Prague, Berlin, and Moscow. There, he was mistaken as a member of a nihilist group that assassinated the tsar. Dadas was imprisoned, but luckily, his punishment was to be exiled to Turkey. Therefore, he traveled to Constantinople, which actually suited his compulsion. From there, he made his way to Vienna before returning to France. Tissie’s paper was followed by an epidemic of dromomania cases throughout Europe, although it’s unknown whether it acted as a trigger or not. French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot opined that dromomania was caused by latent epilepsy. Others believed that it was hysteria. Whatever the cause, interest in the so-called Mad Travelers died out in 1910, just as quickly as it had arrived.

1 The Halfway To Hell Club

Work was scarce during the Great Depression. People were happy to take any job they could find, and minor concerns like personal safety were often pushed to the side. Despite the economic woes, San Francisco undertook one of its most ambitious construction projects during that period: building the Golden Gate Bridge. As you would expect, building what was then the longest suspension bridge in the world caused a few accidents. The number was exacerbated by the fact that many of the ironworkers were completely inexperienced. Since the job paid good money, it attracted numerous unemployed people, all desperately looking for work. The majority of these “ironworkers” were actually farmers, cab drivers, stevedores, clerks, and lumberjacks who lied about their qualifications. Back then, a few dozen deaths on a project of this magnitude were expected. However, chief engineer Joseph Strauss was concerned with worker safety, and he instituted policies to protect his employees. For starters, workers had to wear hard hats at all times, and anyone caught drinking on the job was fired on the spot. Most importantly, though, Strauss installed a $130,000 net under the bridge to catch falling workers. It was brand new safety feature at the time, and the net saved 19 men. These lucky survivors were collectively known as the “Halfway to Hell Club.” Workers were so thrilled with the net that they had to be threatened to not jump into it on purpose. Radu is a history/science buff with an interest in all things bizarre and obscure. Share the knowledge on Twitter or check out his website.