Wrong! In fact, our bodies contain 30–50 trillion extra cells which belong to the bacteria living in your intestines. However, these bacteria are rather small, weighing a measly 1.4 kilograms (3 lb) altogether, a minor part of human body weight. Small as they are, we should be thankful to have them as they improve our health in numerous and surprising ways. In fact, the bacteria in our guts, collectively known as microbiota (or microbiome to include the bacterial genes), are so important for our well-being that the National Institutes of Health launched the Human Microbiome Project back in 2008. The days when bacteria were considered only as little bugs causing disease are behind us. Let’s explore some of the most fascinating facts about the microbiota and see how important your intestinal bacteria are for your health. Also, we will see how to encourage the good bacteria in your system and, if you are a healthy person, whether your stool might be useful for somebody else!

10 A Healthy Microbiome In A Healthy Gut

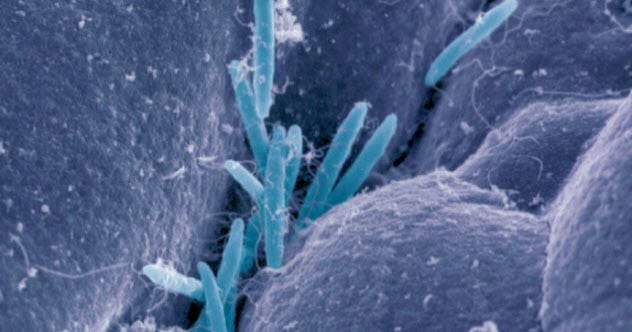

The first obvious place to look at the effects of gut bacteria on our health is in the gut itself. Recent research has shown that good bacteria interact with the epithelial cells lining the gut and the cells of the immune system that fight the bad bacteria such as Salmonella. Salmonella evokes a strong inflammatory reaction, which is in itself a good thing as this helps to attack and destroy the microbe. Unfortunately, inflammation can also damage healthy gut tissue. The good bacteria put the brakes on inflammation by communicating with cells of the immune system. These cells then start to secrete anti-inflammatory molecules to reduce inflammation. The good bacteria ensure an optimal balance between the inflammatory reactions that attack bad bacteria while leaving healthy gut tissue and food alone. As a result, the intestines are in optimal shape to nourish our body.[1]

9 Allergies

Food allergies have increased by about 50 percent in children since 1997. Various theories have attempted to explain why, and the one gaining the most traction right now concerns changed eating habits and, hence, altered microbiome composition. Did you know that today’s American children have had on average three antibiotic treatments, killing off many of their gut bacteria, before they are three years old? Laboratory studies in mice have shown that antibiotics given early in life increase the risk for food allergies dramatically. When these mice are fed Clostridia, which are naturally occurring bacteria in mice, the food allergies disappear. These bacteria protect the lining of the intestines and thereby prevent the entry of reaction-causing food proteins into the bloodstream. Other healthy bacteria such as Bacteroides do not have a protective effect. It seems that each bacteria species plays a unique role in immune responses, such as those involved in allergies.[2]

8 Cancer Immunotherapy

Cancer immunotherapies activate the immune system to attack a tumor. The outcome of the therapy varies from person to person. The bugs living in your gut are a determining factor in how successful the therapy will be. As a rule of thumb, the more variety in your microbiome, the better you will respond to immunotherapy. The species of bacteria in the gut is also important. The presence of bacteria known as Clostridiales and Akkermansia will likely lead to a favorable outcome with immunotherapy, whereas the presence of Bacteroidales will more often than not reduce therapy success. People taking antibiotics, which kill a substantial part of the microbiota, respond less well to cancer immunotherapy. Don’t think that the influence of the microbiome on the outcome of cancer therapy is too far-fetched. For liver cancer, the entire biological mechanism connecting the microbiome with the tumor has been described in astonishing detail—complete with cell types and molecules involved. Perhaps clinicians should start looking at how antibiotics are used in cancer patients receiving immunotherapy?[3]

7 And They Lived Happily Ever After

Fruit flies have an average life span of about 40 days (if not eaten sooner by a hungry bird, of course). When scientists fed the flies with a combination of probiotics and an herbal supplement called Triphala, they were able to prolong the life of the flies by as many as 26 days! The flies were protected against diseases of aging, such as increased insulin resistance and inflammation. These effects were caused by the completely altered composition of the microbiota by the probiotics (that are live bacteria themselves). For flies, the secret to a long life therefore lies in the microbiota and the gut. But this may also hold true for humans to some extent because flies and humans share as much as 70 percent of their biochemical pathways.[4]

6 Diabetes

Type 2 diabetes patients know that consuming fiber-rich food can improve their condition. A fiber-rich diet promotes the growth of particular strains of bacteria, which produce short-chain fatty acids. These products of carbohydrates nourish the epithelial cells of our gut, reduce inflammation, and help to control appetite. After 12 weeks of a high-fiber diet, sugar levels in type 2 diabetes patients are much better controlled, weight loss is increased, and lipid levels are improved. The diet can rebalance the gut microbiome, and healthy dieting may thus become an important part of diabetes treatment.[5]

5 Anxiety And Depression

Imagine a life without bacteria in your guts. How would you feel? Probably anxious and depressed with little desire to see friends and family. At least, this is what studies in germ-free mice have shown. You really need those bugs in your system because they are important for how you feel. Their presence influences the molecular biology in your brain, especially in an almond-shaped structure known as the amygdala and in a particular region of the cortex. These brain structures control emotion and mood. Thus, there is a direct link between the bacteria in your intestines and the molecular biology of the brain. Further research is needed to show whether it is possible to alter the microbiome in humans to treat mood disorders—an interesting approach that might put psychiatrists out of business.[6]

4 Nature Versus Nurture

The composition of the microbiome differs from person to person. For a long time, it has been thought that this variability finds its origin in differences in our genes (nature). However, recent research has revealed that genetic variation contributes only 2 percent to microbiome makeup. Instead, diet and lifestyle are by far the most important determinants of microbiome composition (nurture). Of course, this is excellent news. It means that we can change the population of bugs living in our guts by changing our diets or by adopting healthy lifestyles. Try changing your genome. You can’t—it is fixed from birth. But we can change our microbiome, which could significantly improve our health.[7]

3 ‘There’s No Friends Like The Old Friends’—James Joyce

Living in the countryside might be peaceful and quiet. However, the real reason why people living in rural areas enjoy better health than those living in cities is that they can stand stress much better. This is because their immune systems do not suffer from the negative consequences of stress. This is especially true for people growing up in close contact with farm animals. The animals are covered with and surrounded by a whole set of environmental bacteria that no doubt colonize humans as well. In fact, we have been living in perfect harmony with these bacteria for thousands of years. They are old friends that give us a hand in staying healthy.[8]

2 Vaccination With Bacteria

Everybody is familiar with the principle of vaccination. A crippled virus is injected into your body, and the immune system prepares itself for the attack of the real virus some time later. Did you know that it is possible to do something similar with bacteria? For example, mice have been immunized with the soil bacterium Mycobacterium vaccae, which made them more resistant to stress. They were also protected against stress-induced colitis, a typical symptom of inflammatory bowel disease. As compared to classic vaccination, a particular advantage of immunization with bacteria is that the bacteria have a broad beneficial effect on the immune system and inflammation. Bacteria have other benefits for human health as well. In contrast, vaccination is directed against one germ only. When we think about all this, it seems absolutely astonishing that your whole immune system works better thanks to a simple injection of bacteria. This may even be a treatment option for autoimmune diseases and allergies.[9]

1 Fecal Transplant

Considering all the beneficial effects of the proper gut flora on human health, it is not surprising that there is strong interest in fecal transplantation—the transfer of stool from a healthy to a diseased person. Gross as this may seem at first, did you ever think about the stool of patients with colitis? We won’t go into detail here, but it is not a pretty sight. People are more concerned with the safety issues associated with fecal transplantation. As there are few long-term studies on the effects of fecal transplantation in humans, it is not clear if the positive effects observed in the short term will be sustained over time. Also, the risks of any long-term negative consequences, such as infections, are unclear. Under Canadian and US regulations, the stool used for fecal transplantation is a biological product and drug. If strict safety measures are observed, it may be used for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infections when other treatments are unsuccessful. Results are quite promising. However, clinical results with fecal transplantation for the treatment of irritable bowel disease are not as clear yet. This is probably because there are many factors involved in this pathology.[10] Nevertheless, studies are under way to explore the role for the gut microbiota in many other conditions, such as liver disease, colorectal and other cancers, and even autism. Erwin Vandenburg is a scientist and one of the founders of sciencebriefss, an organization aiming to present new scientific knowledge in a concise and clear manner to the general public.