Bermuda is more than just a certain eponymous triangle. The archipelago has an interesting history, rich culture, and many beautiful sights. Here are some of the most intriguing facts about Bermuda.

10 There Were Devils Here—Or So Sailors Thought

Bermuda was first discovered in 1505, but for years afterward, the Spanish and Portuguese sailors who passed the islands weren’t too keen to row ashore. They didn’t fancy their chances against the treacherous reefs, but almost as frightening were the strange sounds that emanated from the islands as dusk fell. It sounded like hundreds of babies screaming out in unison, and the superstitious sailors continued on their way to safer harbors. It didn’t take long for stories to proliferate about the demons, sea monsters, and witches that haunted Bermuda. The howling infants were, in fact, cahows (aka Bermuda petrels), an endemic species of seabird. They return every year to form dense nesting colonies, and their eerie calls are a way of attracting other birds to breed. They are thought to have once numbered over 500,000 birds. Unfortunately for the cahow, in 1563, Spaniard Don Pedro Menendez de Avila plucked up the courage to sail into Bermuda while looking for his son, who had been shipwrecked. There was no sign of his missing heir, but he left behind some hogs to help sustain the victims of future shipwrecks. The hogs were an ecological disaster, wiping out most of the birds.[1]

9Bringing A Bird Back From The Brink Of Extinction

In 1609, the Sea Venture was en route to Jamestown when it sailed into a storm, possibly a hurricane. The vessel, damaged and leaking, was deliberately ran aground on the reefs off Bermuda. The desperate survivors were delighted to find that Bermuda had been stocked with pigs, since food was scarce in their temporary home. They also supplemented their pork diet with the remaining cahows while they built ships to sail on to Virginia. Since the birds evolved without any mammalian predators, they were remarkably easy to catch and kill. The rats that had jumped ship laid waste to more of the bird population. The birds were thought to have been extinct as a breeding species for 330 years (except for a handful of possible sightings). But in 1951, a scientific expedition went to the islets around Castle Harbor, where seven burrows were finally found. One of the expedition members was a schoolboy named David Wingate. Wingate was fascinated by the rediscovery of the Cahow, and after completing his degree, he went on to save the species, creating a sanctuary for the birds on Nonsuch Island and working tirelessly to protect the cahows for five decades. After years of painstaking conservation work, there are now over 100 pairs of birds (although it’s still the second rarest seabird in the world).[2]

8 You’re Only Ever A Mile Away From The Ocean

As previously mentioned, Bermuda is actually an archipelago, made up of seven main islands and a multitude of smaller islets. It’s just 39 kilometers (24 mi) long and has an average width of 1.6 kilometers (1 mi).[3] From the air, it looks like a fishhook. On the ground, you don’t notice the individual islets much because of the bridges linking them seamlessly together. You can see the ocean from almost any vantage point (the highest point in Bermuda is just 69 meters [225 ft] above sea level), and no more than a 1.6-kilometer (1 mi) walk will bring you within toe-dipping distance of the deep blue. Since the islands comprise just 54 square kilometers (21 mi2) but have a population of around 65,000, the government has had to be draconian to prevent traffic gridlock. Residents are only allowed by buy one car, and tourists can’t rent cars—they have to use the bus.

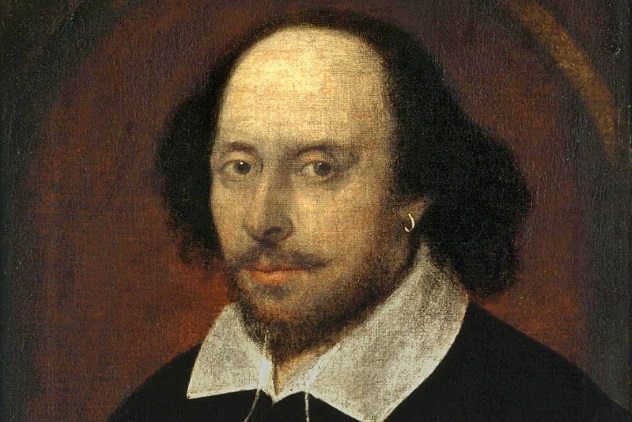

7 Bermuda Inspired Everyone From Sir Walter Raleigh To William Shakespeare

The first person to write about Bermuda was Gonzalo Fernandez, who described the island’s “flying fishes [ . . . ] and fowles called mewes and cormorants” in 1515. The adventurer Sir Walter Raleigh followed up with talk of its “hellish sea for thunder, lightning and storms.”[4] The weather remained a source of inspiration, with Poet John Donne popping it into a 1597 sonnet called “The Storme”: “Compared to these stormes, death is but a qualm / Hell somewhat lightsome, the Bermudas calm.” But Bermuda hit the heavyweight literary headlines when Shakespeare used the islands as a template for The Tempest. His imaginary island might have been based in the Mediterranean, but it was filled with pigs, noisy birds, and a drink made of cedarberries. (Early settlers were reduced to making liquor out of whatever they could get their hands on, and Bermuda had a lot of cedar trees.) Shakespeare’s island could only really be Bermuda. The Bard might have only imagined the island, but Irish poet Thomas Moore set foot on it in 1804 and wrote, “Oh! could you view the scenery dear / That now beneath my window lies,” while Americans might be more familiar with Mark Twain’s musings on the isle—he published regularly in The Atlantic Monthly and helped to make Bermuda a tourist destination. Eugene O’Neill, Noel Coward, and Rudyard Kipling all passed through, too, drawing inspiration from the islands as they went. One of the most influential books from Bermuda was narrated by Mary Price, a slave. The History of Mary Price helped to end slavery in the British Empire.

6 Bermuda Had No Human Inhabitants

There were no native people on Bermuda, so the wreck of the Sea Venture marked the beginning of human colonization. However, most of the settlers left as soon as they had cobbled some new ships together. Just three stayed behind. The founding of Bermuda is commemorated in its flag, the only one in the world to depict a sinking ship.[5] In 1612, the founders were supplemented with a new population when a ship called the Plough arrived with the express intention of settling Bermuda. Over time, new settlers began to trickle in, particularly the Portuguese from the Azores. African slaves came, too (slavery was only outlawed in 1833), and so did a surprising number of Native Americans, exiled to Bermuda or sold as slaves. That mixture of cultures created some deeply rooted traditions, from the Gombeys dance troupe with their colorful costumes to spicy ginger bread, Dark ‘n Stormies (a rum and ginger beer cocktail that packs a spicy punch), and codfish for breakfast. St. George’s remains the oldest continuously inhabited English town in the Americas. Bermuda itself is still a British Overseas Territory. Life was not easy for early settlers; finding water has always been a challenge. There are no rivers and only a few wetlands and seasonal ponds. Even today, Bermudians have no municipal water systems. Instead, they collect water using the specially designed white roofs on their houses, which channel water into underground tanks. If they run out of water, or their tank gets contaminated, they pay heavily to bring water in.

5 Bermuda Is The Shipwreck Capital Of The World

Bermuda is formed from an extinct volcanic mountain range topped off with limestone. As a result, it has miles of fringing reef in every direction, lurking just below the surface. This extensive reef, combined with regular and forceful storms, results in the perfect conditions for shipwrecks. There were over 30 in the vicinity of Bermuda before 1600. To date, more than 300 wrecks have been found. The largest is the Cristobal Colon, a luxury liner which was wrecked in 16 meters (52 ft) of water in 1936 and is a fascinating place to dive. If you’re not a diver, you can snorkel several sites. The Constellation and the Montana were both wrecked in Western Blue Cut. The former was a wooden schooner which crashed into the reef in 1943 while heading to Bermuda for repairs, spilling her cargo of cement, whiskey, and medical supplies (including thousands of ampoules of morphine) into the water, where they still lie at about 7.6 meters (25 ft). The Montana was an efficient paddle steamboat that met her end on her maiden voyage in 1863 after missing the easy approach to St. George’s harbor and trying to take a shortcut through the reef. She was meant to be a Civil War blockade runner and had several aliases to try to confuse the enemy. The Lartington is also close by; it sank in 1879.[6] Since the wrecks are not in especially deep water, it’s possible to see them when you’re snorkeling. You’ll need to take a tour boat to get out there, but there are plenty of companies offering excursions.

4 New Year’s Is Celebrated With An Onion

Bermuda used to export onions—and lots of them. The islands were famous for growing some of the best in the world, and in the late 19th century, the trade was booming, with the vegetable becoming not just a staple but a cash crop, traded with the US and the UK. The word “onion” came to be synonymous with “something super cool” on the islands. Predictably, US growers quickly got wise. They planted their own onions, marketed them as “Bermuda onions,” and sold them minus the expensive costs of shipping. By 1923, exports had dropped from 153,000 crates at the peak to just over 21,000 annually as the Bermudian farmers were undercut. Still, the legend of the onion lives on at New Year’s, where, upon the stroke of midnight, a giant onion, fully decked out in lights and topped with palm tree fronds, is “dropped” from the Town Hall in St. George’s Town Square.[7] If a Bermudian can’t make it to the St. George’s celebrations, they will rifle through the fridge on December 31 to reenact this tradition with a real (albeit smaller) onion.

3 Bermuda Has A Worm That Glows When It Gets . . . Er . . . Hot

The Bermuda fireworm is unremarkable during the day. It is small, reddish, and covered in little bristles that sting if you touch them. When it gets revved up, however, something remarkable happens. In the summer months, on the third night after the full Moon, 56 minutes after sunset (yes, it really is that exact), the worms go bonkers. Females start swimming up from the bottom of the sea, ready to mate and literally glowing with passion. Their bioluminescence switch is set to “max” in a bid to attract a mate. Soon enough, the males hurry over to join the ladies’ neon circles, making the ocean spark with green light. If you want to check it out, try Ferry Reach Park.

2 Introductions Haven’t Gone Well Here

Ah, humans—is there nothing that can stop them messing up a perfectly good ecosystem? Before the arrival of man, a forest of endemic trees and mangroves lined the coasts of Bermuda. The cahow, the Bermuda skink, and a host of unique invertebrates also called the islands home. The pigs, and then the humans and the rats that came with them, all played havoc on the wildlife, and multiple species quietly went extinct. The situation wasn’t helped when people decided to introduce species to control other creatures. The great kiskadee was brought in to control Anolis lizards in 1957. It didn’t work, and the kiskadee went on to threaten native bird species, including the white-eyed vireo and the native bluebird. The birds also spread the seeds of invasive plants and are suspected of extirpating the Bermuda cicada. People also introduced sparrows and starlings, since they reminded them of home. Almost a quarter of the worst invasive species in the world live in Bermuda, including the red-eared slider terrapin, kudzu vine, and Brazilian pepper tree.[9]

1 Bermuda Is Not In The Caribbean

Really. It’s not. Everyone thinks Bermuda is just a stone’s throw from Jamaica or Cuba, but in fact, it’s much further northeast. It’s at roughly the same latitude as Charleston, South Carolina, and is over 1,200 kilometers (750 mi) from the nearest Caribbean islands (the Bahamas).[10] It’s actually closer to North Carolina’s Cape Hatteras than it is to the Caribbean. Bermuda stays warm due to the Gulf Stream and has the northernmost coral reefs in the Atlantic. Helen Raine is a writer and conservationist who has undertaken fieldwork in England, Malta, Peru, Zambia and Hawaii, often living for months in a tent. Her adventures in bird ringing and conservation continue to take her around the world. As a freelance journalist, she has published hundreds of travel articles on adventure destinations for inflight magazines and travel supplements. Find her wildlife books at www.toptenwildlife.com.