10 General David “Dado” Elazar

The Yom Kippur War lasted from October 6-25, 1973 and was initiated by an Islamic alliance of Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and Iraq, against Israel. Their purpose in beginning on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of Judaism, was to declare the hostilities a holy war between two religions. Ramadan occurred during the war as well. The Israeli military was led chiefly by Moshe Dayan, and his immediate second-in-command, David Elazar. Israel won, but suffered terrible casualties, including 400 tanks, 103 aircraft, and almost 3,000 dead. Though the victory was sure and globally impressive, Israel’s civilian population was outraged at its losses and demanded that someone take responsibility. Rather than blaming the collective military or the government, facing the public, and telling the truth, they placed the blame on Elazar, who was the most senior officer to have direct control of the tactical situations in all parts of Israel. Elazar had already shown himself to be a fearsome adversary for Israel when he ordered air and artillery strikes on Lebanon and Syria in open retaliation for the Munich Massacre. He was not afraid to let it be known that the Jews would not tolerate what they viewed as hate crimes. When Egypt and Syria launched combined attacks from opposite sides of Israel on Yom Kippur, the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) was taken completely by surprise, and had no real excuse for this, since Elazar was the primary voice of warning that land and air forces were building up at the borders. He saw it coming. The whole world did. But the IDF did not. Elazar requested permission to order a preemptive airstrike against the Egyptian tanks, but was refused. He did not lose his head throughout the war, nor make rash or hasty decisions, but always worked the problems set him and may be most directly credited with Israel’s maintenance and victory. He asked for the national reserves to be thrown into the fray, and was refused. Nevertheless, the Agranat Commission was convened one month after the war, and voted to remove Elazar from command for causing such atrocious casualties. He quit before they could. The commission at first persuaded the public, but as details emerged of Elazar’s management of the military, he gradually became a champion of the nation’s defense.

9 Admiral Husband Edward Kimmel

By the time the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the top brass in Washington, D. C. knew perfectly well that such an attack was imminent. A conspiracy theory persists that Roosevelt even knew where and when it would happen and deliberately did nothing, because he knew a good, strong war would bring the economy out of the dumps. That theory may not be true, but it is true that Husband Edward Kimmel was made Commander of the Pacific Fleet in February of 1941 and immediately voiced his opinion that “a surprise attack (submarine, air, or combined) on Pearl Harbor is a possibility, and we are taking immediate practical steps to minimize the damage inflicted and to ensure that the attacking force will pay.” What he meant by the last part was not an intent to beat off such an attack, since he did not believe this would be possible from a stationary position in harbor. But he intended to keep the fleet of battleships and company in the shallow harbor so that if they were sunk, they could be easily brought up. To send them out on maneuvers in the open sea to avoid detection might not have worked and would have resulted in them sinking to several miles. The US Navy’s war theory at the time still centered on battleships slugging it out with giant guns, but modern, fast aircraft carriers with fighter-bombers had long since nullified this. Battleships were obsolete. The US was lucky to have sent its carriers on maneuvers, two of three to Wake and Midway Islands. The navy could not agree on where the Japanese would strike first, whether Pearl Harbor, the West Coast, or the Aleutian Islands. Kimmel had this to say about the situation: “Of course they’ll try for Pearl. It’s where all the targets are.” But in the wake of the disaster, the American populace was outraged, and the Navy decided that someone needed to be blamed. They chose Kimmel, who was in charge of Pearl Harbor, for various reasons, most important among them that he kept all the battleships and cruisers in tight arrangements, making them ripe for destruction. He was removed from command and demoted two stars to rear admiral, on the charge of dereliction of duty. This was a severe punishment and one which caused him deep distress for years. His family persuaded the Senate to resolve, in 1999, that he be exonerated and reinstated to four-star admiral. All presidents since then have refused to grant the request.

8 Admiral John Byng

The British Royal Navy had, by the 1700s, already cultivated a reputation as the most formidable and feared in the world, and they prided themselves on this. So when the British lost the occasional naval battle, the public was as outraged as the Admiralty, and the blame game was much worse than with the Army. Byng was in charge of Minorca Island, east of Spain in the Mediterranean. When the French fleet sailed to attack the British garrison stationed there, the British fleet sailed to head them off. The Battle of Minorca was fought on May 20, 1756 (the year Mozart was born) and resulted in a tactical French victory, even though Byng maintained the weather gage (which meant he kept his fleet upwind of the French, a huge tactical advantage). This advantage was insufficient against the French ships, which were far more heavily armed than the British. By the battle’s end, the French had severely damaged about half of the British ships of the line and received very little damage themselves. No ships were sunk on either side. Byng deemed his fleet no longer seaworthy and inadequate to relieve the garrison, and withdrew from the field. The French then besieged Minorca and forced the British to surrender. Criticism of Byng was so sharp throughout England that he was court-martialed and sentenced to death for “failing to do his utmost” to defend British soil. There was a law on the books at the time which required the death penalty in such cases. The Lords of the Admiralty requested from King George II that Byng be granted clemency. George felt personally humiliated by the battle and was further angered when the Prime Minister, William Pitt, made the request. He and the king did not get along, and when George was informed that the House of Commons wanted mercy for Byng, George stated, “You have taught me to look for the sense of my people elsewhere than in the House of Commons.” The public gradually saw the whole debacle as an attempt by the Navy to draw attention away from its own responsibility for the defeat, and demanded that Byng’s sentence be commuted. Now the king had no one defending his decision to execute Byng, but still refused all dissuasion rather than relent to Pitt. Byng was taken onboard the HMS Monarch and on March 14th of the next year, shot dead before the entire crew.

7 The Abu Ghraib Prison Scandal

From late 2003 to early 2004, American military guards assigned to Abu Ghraib Prison, 20 miles west of Baghdad, engaged in an orgy of torture, rape, and humiliation of Arabic prisoners in order to vent their anger over the war in Iraq and 9/11. When the scandal came to light, it showcased the whole world’s emotions over 9/11 (which killed citizens of over 90 nations), when most decried the abuse as horribly unethical, but many championed it. The man most responsible was Specialist Charles Graner, who served 6.5 years in prison for his crimes. The seven soldiers punished were found guilty of sodomizing the prisoners with foreign objects, including a flourescent light that was shattered after insertion. But the worst crime was the torture and murder of Manadel al-Jamadi. He was imprisoned on suspicion of bombing a Red Cross compound, killing 12. Other prisoners testified that al-Jamadi was scared to death as he was brought in for questioning and would certainly have complied without the need for aggression, but he was still beaten severely with punches to the face and chest, kicked in the groin, stripped naked and hung from his wrists with his arms tied behind him from the bars of a window. On inspection 30 minutes later, he was found to be dead. An autopsy discovered that a blood clot had traveled from a wound to his brain. Several soldiers on duty at the prison photographed themselves posing with thumbs up over his corpse. Though the seven soldiers most responsible for the entire prison scandal were punished, no one has ever been formally charged with al-Jamadi’s murder. Attorney General Eric Holder has stated that no one ever will be.

6 Dr. Samuel Alexander Mudd

The operative phrase throughout this entry is “reasonable doubt.” Mudd was the medical doctor who set John Wilkes Booth’s broken left fibula and splinted it with makeshift equipment. He also fashioned some crutches for him. The assassination of Lincoln set the whole nation, and much of Europe, alight with a demand for justice. Here, the word “justice” is used very loosely. The public—North and South—wanted revenge. After Booth was shot down, eight people were tried by a military court that found all eight guilty and sentenced four to hang, three to life in prison, and one to six years. Mudd was given life and sent to Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas Archipelago, 70 miles west of the Florida Keys. Life there was horrible, and Mudd contracted a persistent lung ailment of an uncertain type which plagued him for the rest of his life. Yellow fever killed dozens of prisoners and guards, including the prison’s doctor, and Mudd took over his duties, single-handedly stopping the epidemic. The prisoners, and even some of the guards, petitioned President Johnson for Mudd’s pardon, stating that Mudd did not belong in prison. He was released March 8, 1869, having served four years for doing nothing other than his job of upholding the Hippocratic oath. The court convicted based on witness testimony, much of which was hearsay, without any hard evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Mudd knew of Booth’s conspiracy to assassinate Lincoln. They had met on a number of occasions before, but whether Booth ever told Mudd what he was up to could not be conclusively proven.

5 Lance Corporal Jesse Robert Short

On September 9, 1917, in the military training depot at Etaples, France, some 15 miles south of Boulogne-sur-Mer, the Allied soldiers staged a mutiny against the intolerably harsh conditions the depot imposed on them. This was meant to be a training ground for resisting chemical weapons attacks and teaching various aspects of trench warfare, but not only were new recruits sent through it, even wounded veterans returning from the front lines were forced to undergo the grueling regimens. They were forced, wounded or not, to march for hours every day at the double-quick step. Anyone who collapsed from exhaustion was imprisoned in the stockade and placed on half-rations, sometimes quarter-rations. The hospital’s medical treatment would have been adequate if not for all this training. The wounded required rest in clean conditions in order to heal, but were routinely housed in squalid barracks with the unwounded. Disease was rampant, and all letters of complaint apparently went ignored or never reached the various high commands. The mutiny pitted the soldiers against the military police assigned to keep order within Etaples. The soldiers were not allowed shore leave to the town of Le Touquet, and New Zealand infantryman A. J. Healy was arrested for what was perceived as a bypass of the police barricade. This caused tensions to boil over. The soldiers crowded around the depot end of a bridge and demanded various rights and considerations. The military police arrived as a show of force, but this enraged the soldiers even more and fighting began. The police fired into the crowd and one soldier was killed. The police fled into the town. The protests and fighting continued for three days, when a detachment of soldiers armed with clubs restored order. Trials were immediately convened, one of them charging Short, a New Zealander, with mutiny, for ordering his men to lay down their arms and attack a captain bare-handed. Short was executed by firing squad on October 4th. Whether he was guilty was not the heart of the matter. The cause of the mutiny was obvious, but the training depot remained in operation until the end of the war, and its draconian squalor did not abate, nor was anyone ever held accountable for it.

4 Charles Butler McVay, III

McVay was the captain of the USS Indianapolis, which was torpedoed and sunk between Guam to Leyte Island on 30 July 1945 by a Japanese submarine. They’d “just delivered the bomb, the Hiroshima Bomb,” according to Quint. Of the 880 men who went into the water, only 321 were rescued. The sharks took the rest during a period of four days, mostly scavenging corpses. The American public was infuriated to hear of the Navy’s apparent abandonment of the crew and demanded answers. The Navy was quick to place the blame on McVay, who, as skipper, was most directly responsible for his men. He stated to his officers that he hoped the sharks would get him while floating in the water. During the investigation, he was reprimanded primarily for failing to swerve properly to make his ship more difficult for a submarine to hit. The Japanese submarine commander, Mochitsura Hasimoto, testified in McVay’s defense, stating that he would easily have been able to hit the ship whether it was swerving or not. The Navy also claimed that no SOS messages were received, which is patently false. Three were received at separate stations, and none were acted upon. The Navy has never admitted to this lie. The mission to deliver the atomic bomb components was so top-secret that almost no one on board, including McVay, had any idea of its existence, but the ship’s path, arrival, and departure were known on official maps. The Navy was supposed to announce the arrival, or missed arrival, of the ship at Leyte, and never did so. The crew adrift in the open sea was only discovered by chance when a PV-1 Ventura flew over on routine patrol. McVay was court-martialed and stripped of his rank, but Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz reinstated him when the public’s outcry in his defense became hard to ignore. McVay did, however, receive hate mail and death threats for the rest of his life due to the stigma the Navy imposed on him. He committed suicide in 1968.

3 Edward Donald Slovik

Slovik remains the only American soldier since the Civil War to be executed for cowardice and desertion. He was a petty criminal who had been paroled twice from prison. Most importantly, he was drafted into the Army against his wish, having just married. On October 8, 1944, he asked for permission to refuse front-line duty and was warned not to say such things. The next day, he deserted and gave a note explaining himself to a cook at headquarters. He was finally taken to a lieutenant colonel who promised that he would not be punished if he changed his mind and fought, but he staunchly refused and requested a court-martial. His unit was about to begin fighting in the Hurtgen Forest, where the US Army experienced its worst combat in history. He thought he would only be imprisoned for the remainder of the war. Instead, faced with a rapidly rising number of desertions, the Army sentenced him to death. He pled to General Eisenhower and was refused clemency. Major General Norman Cota defended the Army’s decision, vilifying Slovik as “a coward of the lowest order.” Slovik was executed by firing squad on January 31, 1945 outside Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines, France. A volley of 11 .30-06 bullets peppered his chest and somehow did not kill him immediately. He died after three minutes of asphyxiation and exsanguination. He had stated, “They’re not shooting me for deserting the United States Army . . . They’re shooting me for the bread and chewing gum I stole when I was 12 years old.” Family and supporters have petitioned every president since 1945 for Slovik’s exoneration, none of whom have granted it.

2 Harry Harbord “Breaker” Morant

Harry Morant was a British cattleman, horse tamer, soldier, and amateur poet whom the British tried, convicted, and executed for the murder of unarmed Boer (Dutch) prisoners in South Africa during the Second Boer War. That war was among the most brutal of the 20th century, which is saying a lot. The Boer settlers rebelled against what they viewed as tyrannical British colonization, and the British military responded in force. One of Morant’s best friends, Captain Percy Hunt, led 17 British soldiers and 200 armed Africans to a farmhouse about 10 miles north of Pietersburg (Polokwane) where 20 Boer commandos were headquartered. It was a fair fight, as war goes, and Hunt was mortally wounded. The British retreated with him, still alive, but not before the Boers hacked at him with knives. He died before Morant could reach the area, but when witnesses told Morant of the circumstances of his friend’s death, Morant lost his mind and ordered that every Boer guerrilla, commando, and soldier found be summarily executed: no quarter was to be given. He claimed that he issued this order under permission from Lord Herbert Kitchener, the Chief of Staff of the entire British military in Africa. He argued in his defense that Kitchener’s spoken, not written, order had been passed through the ranks to him that Boer soldiers were not to be taken prisoner, but should be killed on sight. It was not until Hunt’s death that Morant made good on the order. He hunted down at least nine men and had them killed. This much is true: Kitchener did say, as witnesses have testified over the years, that no Boer prisoners should be taken; he preferred that they simply be killed. But when Morant’s court martial for the nine murders sent word to Lord Kitchener for clarification of his order, he denied ever having said anything of the sort, and that he would rather the Boers were taken alive if possible. Through various circumstances, witnesses who testified to the contrary were unable to speak until after Morant was executed. During the trial, the Boers attacked the fort where Morant was held, and he and the other soldiers on trial were momentarily freed and armed, and helped beat off the assault. There was a law on the books at the time that stated that the soldiers should have been pardoned for this assistance, but the law was knowingly disregarded. It is now well established that Kitchener, whether in a state of fury or while level-headed, did express his wish that prisoners not be taken. Morant’s last words were, “Shoot straight, you bastards! Don’t make a mess of it!”

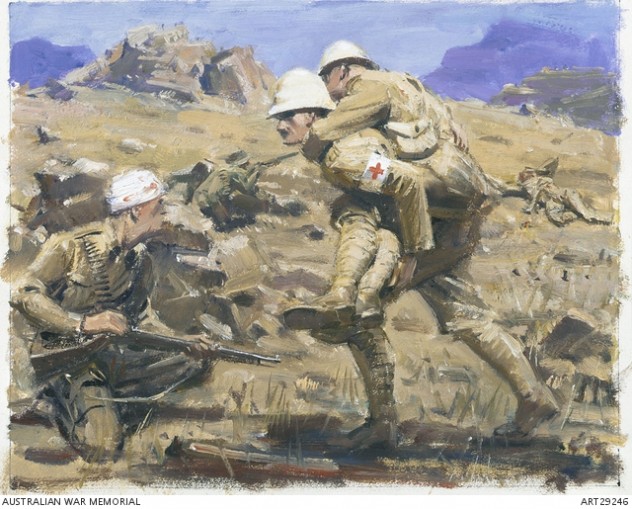

1 Four French Soldiers (WWI)

This travesty can be blamed almost entirely on one man, General Géraud François Gustave Réveilhac, who commanded the French 60th Infantry Divison in World War I. In February 1915, he ordered his men to assault a German redoubt near the commune of Souain-Perthes-lès-Hurlus in northeastern France. The Germans repelled the French three times back across “no man’s land,” through barbed wire, minefields, and muddy shell craters, until finally the French refused to leave their trenches for a fourth assault. This infuriated Reveilhac, who immediately ordered his artillery to shell his own lines, with the purpose of driving the French back out against the German fortifications. The artillery colonel refused this order until Reveilhac sent a messenger to give it to him in writing. Reveilhac’s thinking was that each day a certain percentage of French casualties was expected. If they didn’t reach that percentage, the French were deemed not to be doing their job of pressing on the German positions. The Germans treated their soldiers only a little better. When the fourth assault also failed disastrously, the French high command requested an explanation for the numbers of dead and wounded. To save himself, Reveilhac simply placed the blame on four soldiers, chosen at random from his division. They were charged with “mutiny and gross cowardice in the face of the enemy, resulting in the unnecessary loss of French personnel.” They were tried, convicted, and executed, without the provision of a defense attorney. The families of these four men sued the French government, which paid two families a single franc each, and the other two families nothing. Reveilhac was nominated Grand Officier du Legion d’honneur, and died in his bed in 1937 at the age of 86. FlameHorse is a writer for Listverse.