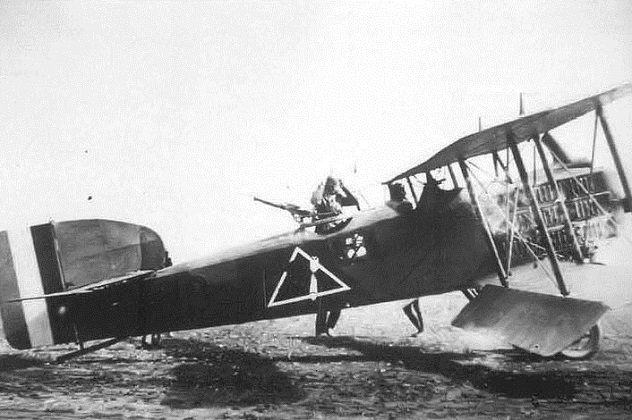

10The Lost Squadron Of World War I

On July 10, 1918, Major Harry Brown of the US 96th Aero Squadron knew his men were itching for a fight. Though their planes had been fueled and armed, the weather had still not cleared up by late afternoon, so the men busied themselves playing poker or contemplating an excursion to a nearby town. When the clouds lifted briefly, Brown decided it was a good time to conduct a bombing run. He had led six planes into the air before the skies once again became overcast. The men could hardly see the ground below. The winds began to pick up, blowing the planes off course, and Brown signaled to the men that they were lost. Since pilots at the time didn’t carry parachutes, they had no choice but to land their planes. To their horror, they ended up landing in Koblenz, Germany, where they were immediately arrested by enemy soldiers. Later on, a German plane dropped a message on an Allied airfield mockingly stating, “We thank you for the fine airplanes and equipment, but what will we do with the major?” General Billy Mitchell, widely regarded as the father of the American Air Force, later wrote in his diary, “This was the worst exhibition of worthlessness that we have ever had on the front. Needless to say, we did not reply about the major, as he was better off in Germany at the time than he would have been with us.”

9The Unbelievable Underestimation At Gallipoli

We’ve spoken before of how unsynchronized watches doomed the Gallipoli Campaign, but the tragedy that befell the brave Anzacs and other Allied forces in Gallipoli might have been months, if not years, in the making. For one thing, previous war plans concerning an amphibious assault on the Dardanelles called for operations that needed to be fully practiced and drilled using the best military equipment available at the time. Instead, Churchill and other overzealous British military leaders favored sending aged battleships that ran aground or had mechanical and weapons systems failures. Other plans suggested that any invasion should have occurred earlier when the Turkish forces were unprepared, while some explicitly stated that no attempt should be made to assault the position. When World War I did begin in earnest, the Greeks repeatedly cautioned the British not to be overconfident—an estimated 150,000 men were needed for the landings to be successful. Instead, British planners threw caution to the wind, believing that only half that number was necessary. Similarly, while the British had maps of the area, they had virtually no aerial photo reconnaissance. Lord Kitchener had remarked that “Johnny Turk” would run away once the first Allied soldier stepped foot on Turkish soil, so there would be no need for planes. Of course, he was completely wrong, and the Allied forces met a humiliating defeat at the hands of the Turks.

8The Ill-Advised Invasion Of Kashmir

In 1965, hawkish elements within the Pakistani government and armed forces believed that India would no longer be able to defend the Jammu and Kashmir regions in full force. Pakistan expected support from the United States and China, the former having sold them the latest in military hardware while the latter handed India a crushing defeat during a border war in 1962. Military leaders drafted Operation Gibraltar, which called for thousands of men from West Pakistan to infiltrate the hilly and mountainous Kashmir region with the aim of destabilizing it and inciting the populace to revolt against India. Indian officials claimed that nearly 30,000 men took part in the operation, while Pakistan offered a more conservative number of 7,000. In August 1965, the operation went underway. It seemed to be going as planned until everyone realized that no attempts were made to establish contact with Indian Kashmiris. Local leaders were actually kept in the dark about how the plan was to proceed, so no great revolt ever occurred. On the contrary, the locals actually cooperated with Indian intelligence services in apprehending the infiltrators, who gladly spilled the beans. India broadcasted denouncements of Pakistan’s attack and war plan. Knowing that Operation Gibraltar had failed, the element of surprise was lost, and there would be no support or sympathy coming from foreign powers, Pakistan senselessly decided to launch a full-scale invasion. The entire operation devolved into a stalemate, and the United Nations enforced a ceasefire on September 22, 1965.

7The Empty Camp Of Son Tay

On November 21, 1970, American POWs held by North Vietnamese forces heard the whirring sound of helicopters, missiles, and sporadic gunfire that meant raiders had arrived to rescue them. The team, made up of Green Berets and US Air Force special ops, had 30 minutes to get in, rescue the 60–70 prisoners believed to be held in the enemy camp in Son Tay, and get out. The unit was fully prepared, to the point that different phases of the mission were allegedly practiced 170 times. In those pre-dawn hours, escort aircraft blasted preselected targets while helicopters destroyed watchtowers. The raiders had killed or wounded over 100 enemy forces, yet there were no signs of the American prisoners. Apparently, due to faulty intelligence, military planners had no idea that the prisoners had been moved to another location. All the training hours and money spent on the operation were deemed a waste, and successive hearings scrutinized the failure of the mission to achieve its objective. Despite the raid at Son Tay being a daring but ultimately failed mission, it’s worth noting that it did have a positive effect. Upon their release, POWs recalled the moment they heard the sound of battle nearby, rejoicing in the knowledge that their country had not forgotten them. Years later, these two groups—the rescuers and the once-captive men—would meet and establish the Son Tay Raider Association to commemorate their brotherhood in war.

6The ‘Third Force’ Program

In 2007, the CIA released declassified information regarding a failed program known as “Third Force” which aimed to create a surveillance and special ops network within communist China during the peak of the Korean War. The plan called on Chinese exiles to rendezvous with communist generals who were dissatisfied with Mao Zedong’s government. The goal was to destabilize the region, which would hopefully lead to the Chinese pulling out of the war. On November 29, 1952, CIA operatives John Downey and Richard Fecteau were flying over the Changbai Mountains, seeking their Chinese counterparts. As the plane descended, explosions ripped through the sky as they realized they were being ambushed. There were no disaffected communist generals, it had all been a ploy concocted by their sources in Hong Kong and Taiwan. The plan was so well-known to the Chinese that when an officer spotted Downey, he said, “You are Jack. Your future is very dark.” He wasn’t wrong: By the end of the ambush, their two pilots were dead, and Downey and Fecteau were hauled off for interrogation. The CIA covered up the debacle by claiming that the men died during a commercial flight from Korea to Japan. For several decades, the families of the men believed them dead. In December 1971, Fecteau was released by China as a gesture of goodwill. Downey remained in prison, and no amount of diplomatic maneuvering or pleas concerning his ill mother would convince the Chinese to let him go. In March 1973, however, the Chinese had a change of heart following President Nixon’s public admission that the men were CIA agents and apology for their presence in China.

5The Secret War In The Baltics

For his 1993 book, Red Web: MI6 and the KGB Master Coup, British writer Tom Bower painstakingly researched and outlined the Secret Intelligence Service’s plans to create an espionage ring in Poland and the Baltic States. The operation, which was called “Operation Jungle,” was conducted from 1945–1955, the early years of the Cold War. While a few aspects of the operation were successful, such as the delivery of new motorboats to West Germany, virtually everything else was a failure. On October 15, 1945, British conspirators sent four agents to Latvia for reconnaissance, where their boat capsized and they were captured. Their ciphers and transmitters fell into the hands of Janis Lukasevics, a member of the Latvian KGB. Lukasevics knew that waiting for Britain to send more spies would be risky, so he baited them. One of the prisoners, Augusts Bergmanis, broke under torture, subsequently aiding Lukasevics with the trap. Bergmanis sent false radio reports as well as requests for additional agents, 42 of whom were sent and immediately intercepted by the KGB upon landing. Some were killed, but many were turned against Britain or used to hunt down anti-Soviet forces within the Baltic States. The flawed operation continued for an entire decade until Britain mercifully pulled the plug.

4Operation Lena

Despite Hitler postponing Operation Sealion, the invasion of Britain, an Abwehr agent named Wulf Schmidt parachuted into England five days later on September 14, 1940. Upon landing, Schmidt was immediately apprehended. He was part of Operation Lena, the plan by German intelligence to pave the way for an invasion that would never occur. Indeed, the bumbling operatives may not have made much of a difference due to their sheer incompetence. The operatives were actually so inept that many have speculated that the Hamburg branch of the Abwehr were deliberately sending incompetent agents as an act of sabotage against the Nazis. None of these secret agents were even fluent in English, and they had little to no knowledge of English customs. Other spies were caught, much like Schmidt, because of what British official records bluntly called “their own stupidity.” One operative was arrested while attempting to buy a pint at 10:00 AM, not knowing that pubs could not serve alcohol before lunchtime. Two more were arrested while cycling in Scotland on the wrong side of the road. The men tried to explain their plight to the police in unconvincing English accents, but their covers were blown when it was discovered that their suitcases contained German sausages and Nivea cream.

3General Patton And Task Force Baum

During the closing days of World War II in Europe, the Hammelburg POW camp in Germany was attacked in a daring but futile raid. Members of Task Force Baum—named after their commander, Captain Abraham Baum, and composed of 314 soldiers and 57 vehicles—were tasked with penetrating 100 kilometers (60 mi) of enemy territory to liberate the prisoners on March 26, 1945. The order was given by none other than General George Patton, who believed his son-in-law was a prisoner at Hammelburg. The general’s folly sent hundreds of men on a mission that was doomed to fail. Task Force Baum met heavy resistance on the way to Hammelburg, losing several tanks and an entire infantry platoon. By the time they reached the camp, the contingent had lost 30 percent of its soldiers. Upon arrival, they were blindsided to find that their superiors vastly underestimated the number of prisoners at the camp—they were told there only 300, but they found a staggering 10,000. Two days later, the Germans launched a counterattack. Several of the men tried to run into the nearby woods, but they were the lucky ones. Baum himself was shot in the groin. The task force’s vehicles were all destroyed, 26 men were killed, and only a handful made it back to Allied lines. The rest became prisoners, just like the men they tried to rescue. On April 6, 1945, the US 14th Armored Division finally liberated the camp, rendering the previous mission completely unnecessary.

2The Jablonkow Incident

On the night of August 25, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Aided by Sudeten Germans, Abwehr operatives and commandos crossed the Czech-Polish border to capture Jablonkow Pass. The objective was the railway of Mosty, as well as radio stations, telephone lines, and nearby bridges, which were needed to secure a foothold once the rest of the army arrived. The problem was, it never did. After Hitler received word that Britain and France intended to honor their agreements to defend Poland and Italy was not ready for war, he decided to postpone the invasion. None of this was known to the commandos who were deep behind enemy lines, since they were not issued radios. The elite unit under Lieutenant Hanz-Albrecht Herzner was already prematurely celebrating their victory. They caught the Poles unaware and suffered virtually no losses. The men had used covert tactics and simple intimidation, such as telling the Poles that the entire German army would soon bear down on them, so fighting was unnecessary. They had even captured thousands of Polish soldiers in a troop train. It was hours later, as dawn began to break, that Herzner was able to contact the nearest division stationed within Germany and found out that no help was forthcoming. Herzner and the men had to scurry back to Germany with their tails tucked between their legs as the Poles harassed them at every turn. The Jablonkow Incident, as it became known, was played down via diplomatic means. It was also the last-ditch attempt of the head of the Abwehr, Wilhelm Canaris, and his co-conspirators to remove Hitler from power before the conflict erupted. Canaris and his cohorts tried to pressure military leaders to consider Hitler’s invasion unconstitutional, to no avail.

1Nearly Everything Involving Italy During World War II

Mussolini’s decision to go to war against the Allies was controversial, and virtually everyone urged him to reconsider. The armed forces were not prepared, their equipment was not up to date, and their troops were scattered around the globe. Still, Mussolini insisted, wishing to “sit at the peace table as a man who has fought.” When France’s defeat against Germany was certain on June 10, 1940, Italy invaded. President Franklin Roosevelt denounced the act, calling it “a stab in the back”—though in reality, it was more of a pinprick. The advance of 300,000 Italian soldiers was checked by a handful of Frenchmen. The Franco-Italian armistice demanded far less compared to Hitler’s aims, which historians have pointed out was probably because Mussolini wanted to demonstrate that he was a “good sport” after his armies were humiliated. Despite the many instances when Italy’s forces were numerically superior, they were constantly beaten back by fewer yet more determined opponents. In Italian East Africa, a multitude of soldiers under the Duke of Aosta were rapidly crushed by the British under Generals Wavell and Cunningham. In North Africa, Italian offensives were also blunted. Perhaps there was no bigger blunder than Italy’s ill-timed attack on Greece, which hoped to remain neutral in the conflict. The Italians were pushed back after several months of fighting, eventually requesting Germany’s aid. The change in the timetable caused a chain reaction that included a spirited defense by the locals and the debacle at the Battle of Crete. Hitler’s planned invasion of Russia was significantly delayed for weeks and ground to a halt by late fall of 1941. Despite these setbacks, Italian soldiers distinguished themselves in other theaters. In the Atlantic, Italian submarines played a key role in harassing Allied shipping. Their “manned” torpedoes were a bizarre yet innovative concept. Thousands of men, including expeditionary corps and the vaunted alpini under Giovanni Messe, distinguished themselves in the invasion of the Soviet Union. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s assessment of the quality of the Italian soldiers and their lack of good equipment was more than apt. The “Desert Fox” noted that it made “hairs stand on end to see the sort of equipment with which the Duce had sent his troops into battle.” Rommel also remarked that though “German soldiers impressed the world, the Italian Bersaglieri impressed the German soldier.” There are a lot more daring yet utterly foolish war missions from this time period. If you’ve got suggestions or clarifications, you can talk to Jo via email.