In some ancient societies, though, dead bodies were modified, and parts were kept for ritual, symbolic, or practical reasons. Some corpses were adapted before being buried, either to protect the living or as part of ritual funerary rites. These practices have led to some pretty eerie archaeological finds.

10 Skull Cups

Skull cups have been created by many different cultures, in many time periods. They involve taking the cranium from a corpse and carving it into a usable cup shape. The focus is usually on the top of the skull, known as the calvaria. Sometimes, decorative engravings are added. The oldest skull cups ever found were a trio from Gough’s Cave in Somerset, England, that are dated to 14,700 years ago. These were found in a cave with other human remains that had probably been cracked open to access the bone marrow. Other skulls that were modified and may have been used as cups were found in Nawinpukio in Peru from AD 400 to 700 and from the Bronze Age in El Mirador Cave in Spain. There was systematic production of skull cups during the Neolithic in Herxhein in Germany, and early ones were made during the Upper Paleolithic in Le Placard Cave in France. The Vikings and Scythians reportedly used their defeated enemies’ crania as cups to harness the dead’s power or as a way of asserting their own power. Historical records have mentioned the use of skulls as drinking tools among the Aghori in India and Aborigines in Australia, Fiji, and other islands in Oceania. Tibetan skull cups, known as kapalas, were used by Buddhists and Zoroastrians, who practiced sky burials. In these, the dead would be left exposed for birds to de-flesh, and then wine would be poured into the skull, and it would be sacrificed to the gods.[1]Kapalas still appear on sale today, though the ethical and legal side of it is highly controversial, and many places in the world have banned the sale of them completely.

9 Bones As Tools

Further practical use of skeletons has been seen in the ancient city of Teotihuacan in Mexico. A pre-Aztec society there fashioned a multitude of everyday items, such as buttons, combs, needles, and spatulas, out of freshly deceased human bones between AD 200 and 400.[2] They used the femurs, tibiae, and skulls for this purpose. Stones were used to de-flesh and fashion the tools, and the process must have started shortly after death. Otherwise, the bones would have become too fragile to be worked on. The tools found so far were only made from local young adults; none were made from foreigners, children, or the elderly. A Neanderthal skull bone that is at least 50,000 years old was used as a tool. The bone was found among other Neanderthal remains near the Voultron River in France and was used to sharpen stone tools.

8 Bones As Jewelry

Bones have also been fashioned into jewelry. Human cranial bones were used to make oval amulets with a hole drilled into one end around 3500 BC in Neuchatel, Switzerland.[3] Similar pendants have been found in Port-Conty, La Lance, and Concise, all in Switzerland. Necklaces made from hand and foot bones have been found in Mexico and the Plains and Great Basin in the United States. The bones were strung together, making a long chain, or added to necklaces as pendants. It is believed that they were made from dead enemies to symbolize victory.

7 Bones As Musical Instruments

The Aztecs would make an instrument called an omichicahuaztli out of human bones, using leg or arm bones to make the percussion device. These instruments have been found at archaeological sites across the empire, dating from throughout most of its reign, and were made by creating notches along the bones. Occasionally, this instrument was made from animal bones, such as a turtle scapula or a whale rib. Tibetan Buddhists used a trumpet-like instrument made from a human femur called a kangling.[4] It was a part of Tantric and funerary rites that were meant to remind them that the body is a temporary thing. The bone was preferentially taken from a criminal or someone who suffered a violent death, though if that wasn’t available, it could be from a teacher. The instrument originated in India 1,500 years ago and spread to Tibet in AD 800.

6 Ritual Corpse Mutilation

In modern-day Lapa do Santo, Brazil, some of the oldest human skeletons from the New World have been discovered in a cave deep in the rain forest. People have lived there for 12,000 years and initially buried their dead fully intact. However between 9,600 and 9,400 years ago, funerary practices changed, and the deceased were systematically mutilated.[5] The corpses’ teeth were pulled out postmortem, and they were dismembered and de-fleshed. There is evidence of the dead being burned or cannibalized, with their bones later placed inside someone else’s cranium. No other funerary practices have been discovered from the same time period (such as leaving grave goods, for example), so the mutilation may have been the main ritual practice associated with death.

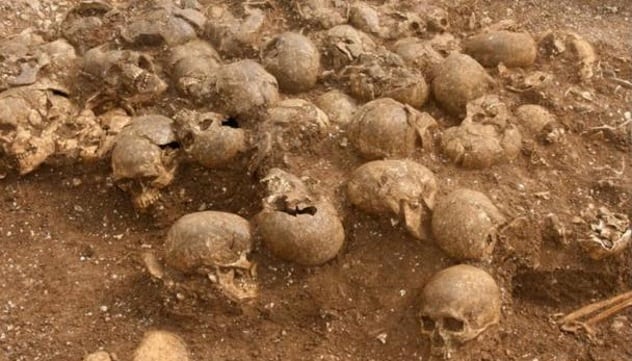

5 Ritual Decapitation

The removal of a body’s head has been practiced across the world in order to demonstrate strength and show off victory over enemies. One of the skeletons at Lapa do Santo had been decapitated after death by twisting and pulling the head off the neck. The head was buried without its body but with the individual’s hands placed over the face, one hand facing up and one facing down. In Dorset, England, a mass grave of 54 Scandinavian Vikings from sometime between AD 910 and 1030 were discovered.[6] They were all males in their late teens or twenties with no evidence of battle wounds. Their bodies were buried together, with 51 skulls buried in a separate pile. The heads had been sloppily chopped off shortly after death and kept separate from the bodies. Three heads were missing and have yet to be found. It is speculated that these belonged to important members of the group and that their heads were brought somewhere else in order for their killers to show that they had indeed defeated the Vikings.

4 Head Shrinking

In order to shrink a head, the victim would be decapitated straight after being murdered. The skin would then be peeled off the skull and then shrunk in a week-long process. This involved boiling it at a very specific temperature for just the right period of time, sewing the eyelids shut, using wooden pegs to keep the mouth shut, filling it with hot stones and sand, and rubbing it with charcoal. Once completed, the head was worn as a necklace. The heads were usually discarded shortly after they had been shown off to the nearby tribes. Later, Westerners appeared and started buying them. Although this is an ancient practice, it continued until the 20th century and was considered a lucrative custom until the sale of shrunken heads was banned in the 1930s.

3 Vampire Treatments

Vampires have been a common fear across the world, resulting in suspects’ bodies being treated in certain ways after death to ensure that they don’t come back and terrorize the living. In Europe, a brick was commonly forced into the dead’s mouth, often breaking teeth, before burial. This was, for example, seen in a 16th-century woman from a plague grave in Venice, Italy. Some bodies were pierced by stakes after death to ensure that the dead were really dead. This was seen in two 800-year-old corpses from Sozopol, Bulgaria, who had large iron rods stuck through their chests. A 700-year-old male from Bulgaria was both pierced through the chest with an iron rod and had his teeth pulled out postmortem before being buried. Across Poland, various bodies have been interpreted as vampires. Two middle-aged women had a rock and a sickle placed across their necks, and a male and female were decapitated before being buried on their sides.[8]

2 Mellified Men

Unlike the other practices listed here, this process was started prior to a person’s death. During the 12th century in Arabia, some men who thought they were nearing death would start to eat and drink nothing but pure honey, also using it to wash themselves.[9] Eventually, this practice would kill them, and their corpse was placed in a stone coffin filled with even more honey. A couple centuries later, their bodies would be retrieved, cracked into small pieces, and sold at a bazaar as healing candy. This practice was written about by Chinese travelers, most prominently by Li Shizhen in his 16th-century compendium of unusual remedies, the Bencao Gangmu. Although there has been some debate as to whether or not this mellification was carried out in reality, there have been human remains found in modern-day Georgia that were mummified in honey 4,300 years ago, Alexander the Great was purportedly preserved in a coffin full of honey, and Herodotus reported that the Assyrians would embalm their dead in honey.

1 Possible Cannibalism

Although this form of modification is not an intentional way to change the body or skeleton, cannibalism still leaves its mark on a victim’s bones. In El Sidron, Spain, there are remains of 12 Neanderthals who were most likely cannibalized by other Neanderthals 49,000 years ago. Their long bones (arm and leg bones) were cracked open to extract the marrow, and there are cut marks on the bones consistent with de-fleshing and disarticulating multiple bones. Researchers have also looked for human gnaw marks on human bones, finding them on 12,000-year-old bones in Gough’s Cave, England. They’ve even found such marks on 800,000-year-old bones from Homo antecessor in Gran Dolina, Spain.[10] This indicates that it wasn’t just Neanderthals who practiced cannibalism. I’m an archaeologist who’s interested in ancient human remains, anything morbid, and history.